BY MELISSA GOMEZSTAFF WRITER MARCH 21, 2023 5 AM PT

Original Source Link: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-03-21/landback-los-angeles-indigenous-school

When Jamie Rocha and her family first visited the swath of undeveloped land in the Monterey Hills late last year, the grass was dead, the ground muddy.

But on a recent Thursday, after drenching rains in Los Angeles, the grass was a rich green and purple lupine lined the path. Coyotes roamed nearby, sniffing the ground before disappearing below the hillside’s sloping edge.

The afternoon calm belied the family’s excitement. On this day, they were walking on what would one day be their land, 12 acres that had been purchased by the region’s only Indigenous charter school and returned to the Gabrielino Shoshone Tribal Nation of Southern California, the area’s original inhabitants.

“It’s mind-blowing, just to have a dedicated space [for] the Indigenous ways and education,” said Rocha, a member of the tribe, which has long struggled to find a place to practice its ceremonies in congested Los Angeles County. “I wish my grandmother was here to see it.”

In August, the Anahuacalmecac International University Preparatory of North America bought the land for $800,000 with the help of grants and nonprofit funding. The K-12 charter school in El Sereno intends to act as a steward for the land and establish the Chief Ya’anna Learning Village.

The complex is named for Ya’anna Vera Rocha, a late chief of the Gabrielino Shoshone Tribal Nation and Rocha’s grandmother.

Having such a space “always seemed kind of impossible,” Rocha said, “because you know, our territory is prime real estate.”

::

Across the street from the now-sacred ground sits a looming condominium complex. The land is bordered on one side by a townhouse complex; there’s a low-income senior apartment complex on the other. It overlooks Elephant Hill Open Space, a 15-acre area free of development but scarred by off-road vehicles.

Still, it feels a world away from the downtown bustle and car horns that make up the cacophony in the heart of Los Angeles.

The land was once a valley in the Monterey Hills before it was filled with dirt from neighboring development, said Marcos Aguilar, who co-founded the school with his wife, Minnie Ferguson. It was at one point owned by the now-defunct Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles and later sold to a developer.

The acreage is home to several types of birds, rabbits and black walnut trees,an endangered species that is found in select parts of the county and used by Indigenous people for tea, food and dye. The land also serves as a corridor for coyotes, and Aguilar said they intend to preserve it in its natural state as much as possible.

The acreage was purchased by the Tzicatl Community Development Corp., the nonprofit organization that runs the Anahuacalmecac school, with funding from NDN Collective Landback Fund, Metabolic Studio and the TomKat Ranch Educational Foundation.

Nick Tilsen is president and chief executive of NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led nonprofit that launched a land-back campaign in 2020. The movement, which has existed for decades, promotes restoring land ownership to Indigenous communities.

In California, land-back movements have been successful. Eureka returned 202 acres of land on the renamed Tuluwat Island in Humboldt Bay to the Wiyot people, who had campaigned for it since the 1970s.

In this case, Tilsen said the coalition moved quickly to fund Anahuacalmecac’s land-back effort.

“When we looked at what was happening in Los Angeles with the school … and what their vision was with the land, in a place with such a limited amount of land left, we were like, ‘Let’s find a way to support this,’” Tilsen said. “This is coming from Indigenous students and Indigenous teachers and Indigenous administrators who are trying to build that radical feature.”

Tilsen, a member of the Oglala Lakota Nation, said there is another Indigenous school in Rapid City, S.D., which purchased 66 acres that it will use to expand the school and community living space.

Rocha said she wishes her grandmother was around to see what the school and the tribal nation had accomplished.

Today, the band has about 150 to 200 members, and Rocha is on the tribe’s council. Over the years, she said, she saw her grandmother’s work fade from L.A. County and state history. But the school has helped keep her grandmother’s legacy alive.

The late chief was part of a vocal group that protested when organizers for the Pasadena Rose Parade wanted to name a descendant of Christopher Columbus as a grand marshal. She and her husband, Manuel Rocha, also led the Spirit of the Sage Council, which fought to protect endangered species and habitats. And she worked to save the Ballona Wetlands in the 1990s.

“My dad said, like, he really wishes my grandma was here to see this just because especially in L.A. County, there’s not really spaces dedicated to us,” Rocha said. “We always had to make our own spaces, whether that was our homes or community centers.

“People think that the land belongs to us,” she said. “It’s quite the opposite. We belong to the land, and we want to get back to the land.”

::

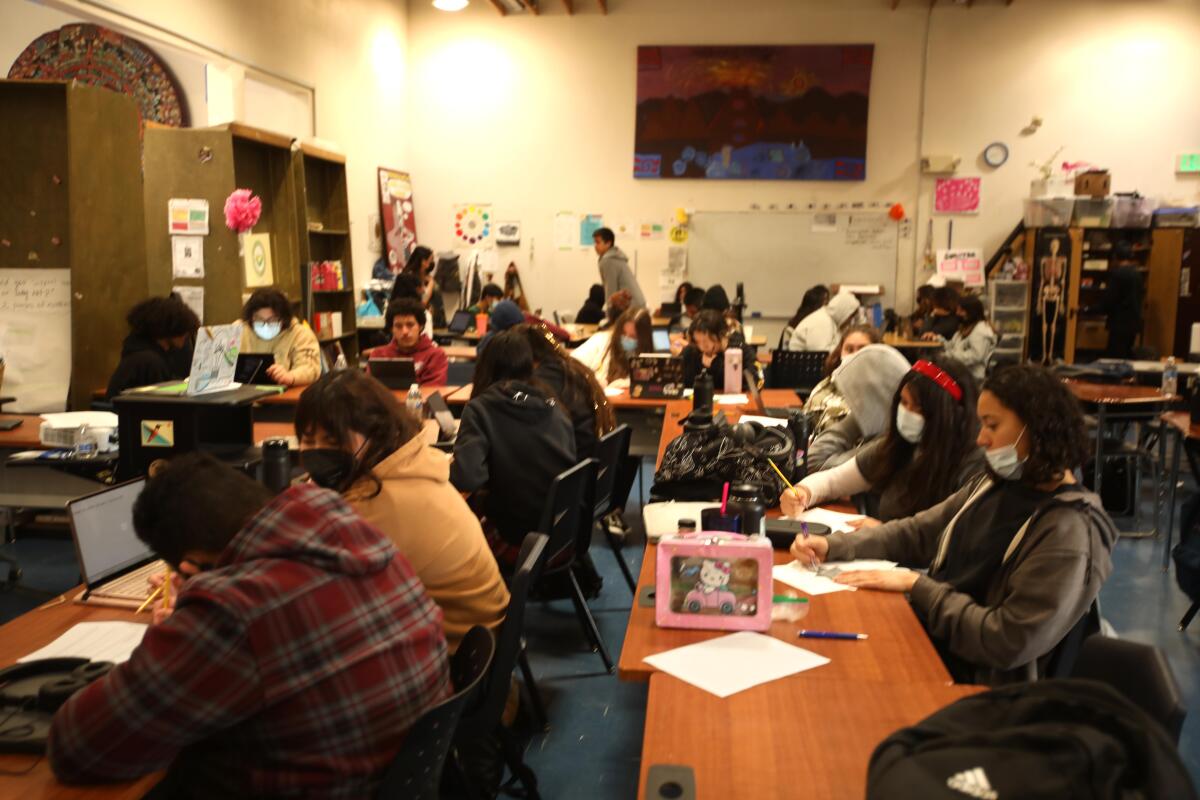

When Anahuacalmecac opened in 2002 in El Sereno, it was with the blessing of Ya’anna Rocha, who was tribal chief at the time, Aguilar said. Since then, the school has grown modestly and now has 260 students across three campuses.

The school teaches a curriculum with a Nahuatl focus. Lessons are taught in English, Spanish and Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs before the Spanish conquest of Mexico.

The school offers an “Indigenous” curriculum with courses such as Global Indigenous Voices, Writing for Social Justice and Leadership and Liberation.

Anahuacalmecac school leaders view the institution’s role as decolonizing education by teaching Indigenous students to embrace their heritage. To do that means centering Indigenous voices and history, which have historically been left out in the origin stories of the Americas.

The Rochas are Gabrielino Shoshone, also known as Tongva people and Natives to California, but Ya’anna Rocha also embraced Indigenous immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

By naming the proposed center the Chief Ya’anna Learning Village, Aguilar said they would pay tribute to the Indigenous leader who treated Indigenous immigrants from Latin America as family. The land is also an extension of the school — students can connect directly with the environment by taking classes on the land.

The school plans to launch a fundraiser later this year to cover the costs of creating the learning village, including designing a cultural center and classrooms on the space.

“The way we think about this is, this is over the next 500 years, so land-back is everything coming back,” Aguilar said. “What we want to do first is get to know what that land is like, how it feels, how life there lives. …

“It’s entirely different today from what it looked like 100 years ago,” Aguilar said. “And so we want to understand that first.”

Axayacatzi Kuauhtzin, a 16-year-old junior at the school, said the space opens up her imagination for what students can create for Indigenous people in L.A. In October, an Altadena resident transferred a one-acre parcel to the Tongva people, the first land-back transfer for the Indigenous community.

“I’m just so grateful to be able to have all of these opportunities open to me, especially in L.A., in such an urban area,” Axayacatzi said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, the school was forced to teach remotely. Now, Aguilar said, school leaders feel they have to help students reconnect with the land around them after coming back from being at home for so long.

“We felt like bringing the teachings to the land and connecting our students with the land around us and around the county would be extremely important,” Aguilar said.

They expanded their partnership with the city’s Department of Recreation and Parks to help maintain its Native American Terraced Garden and later led a reforestation effort with students, staff and the community, planting 300 plants and 500 trees.

Marye Chairez, a junior, said she is excited about the land being used for future and younger Indigenous students, including her sister, who is in fourth grade.

“It’s all about this connection and relation to the language, the land,” the 16-year-old said. “And Ya’anna village will be a legacy of us, the young students, the young activists, that have been here in this school.”

Times staff researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.