Source: https://sustainablecitycode.org/brief/pervious-cover-minimums-and-incentives-2/

Kerrigan Owens (author), Jonathan Rosenbloom & Christopher Duerksen (editors)

INTRODUCTION

This regulation provides local governments with the flexibility to either create incentives, set requirements, or do a combination of both for the minimum use of permeable pavements for certain projects. Local governments may choose the type and size of projects to be subject to permeable requirements or incentives and may choose the appropriate level of permeable surfaces.

Permeable pavement or surfaces refer to any paving system that provides a usable hard surface but also allows for infiltration of water through the surface.[1] Permeable pavements come in a number of different forms, with new technologies and techniques constantly being developed.[2] Such systems include a variety of surfaces, such as pavers that connect to form a surface with small gaps to allow water to pass through[3] and porous concrete that forms a single or multi-slab coarse concrete surface. Porous concrete has a number of small gaps throughout to allow water to flow though the surface.[4] The different types of permeable pavement have unique costs and benefits that developers should consider and that local governments should consider when drafting this ordinance.[5] Some alternatives may be less desirable for high-traffic areas such as highways or areas with significant snow and freezing temperatures that limit permeability.[6]

EFFECTS

Traditional concrete pavement, asphalt, and other impermeable surfaces have a number of potentially adverse environmental effects.[7] While most codes may require some type of paved surfaces, there are several alternatives that can replace or reduce the detrimental effects of impermeable pavement.[8] Doing so may help divert run-off from entering into local stormwater management systems or bodies of water.[9] Local stormwater utilities that often maintain storm sewers and other drainage systems bear the costs associated with impermeable pavement.[10] In addition, run-off can increase flooding either in the municipality or downstream.[11] This run-off may add pollutants to the water requiring additional costs and energy to be spent to remove them.[12] Water treatment is an energy intensive process demanding use of fossil fuels that can result in significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.[13] In addition, reducing the amount of storm water and associated pollutants entering the system can lower water treatment costs.

EXAMPLES

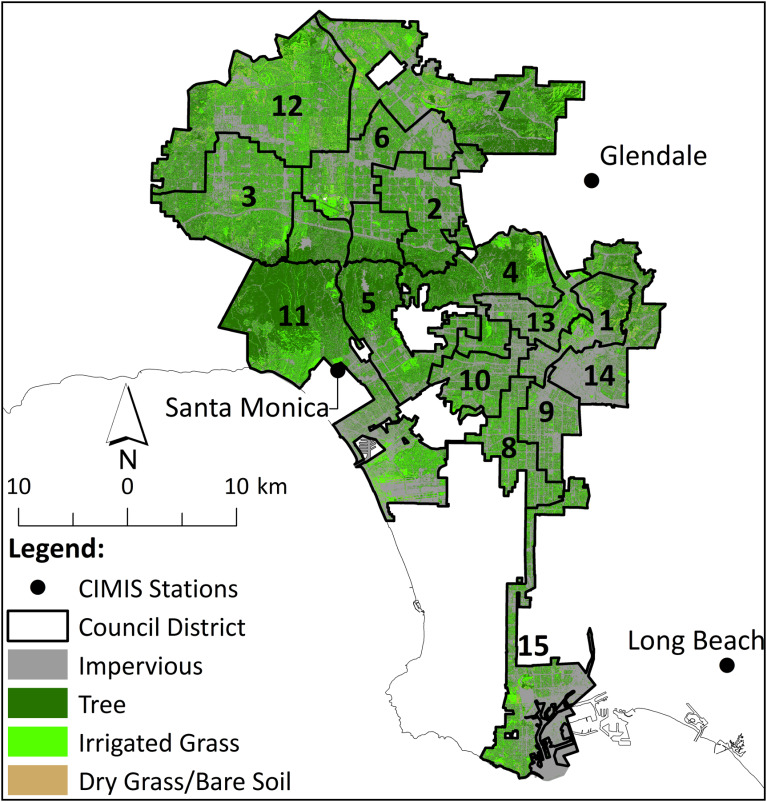

Los Angeles County, CA

Los Angeles County encourages the use of permeable pavement through Low-Impact Development (LID) standards. This ordinance specifically addresses the Santa Monica Mountains local implementation coastal development plan that is working to protect and manage the areas resources.[14] Some of the requirements include minimizing impervious surfaces such as sidewalks, driveways, or parking, using permeable materials when possible, and directing new impervious surface run-off to permeable areas.[15] The relevant provisions provide that a development will be given “preferential consideration for approvals” if using techniques that minimize impacts due to run-off.[16] Several recommended techniques are then set forth in the code including: the reduction of impervious surfaces, the redirection of run-off into permeable areas, and the prioritization of permeable pavement over traditional pavements.[17] A project following these guidelines may reduce run-off and improve water quality.[18]

To view the provision see Los Angeles County, CA, Code of Ordinances § 22.44.1340 (G).

San Antonio, TX

As part of its Low Impact Development and Natural Channel Design Protocol (LID/NCDP), San Antonio encourages the use of permeable pavement by providing both permitting credits as well as a stormwater fee discounts for landscaping, parkland, tree canopy, buffering, and storm water to developers using the LID/NCDP.[19] However, to qualify for this credit the development must be able to manage at least 60% of the stormwater run-off that the development will generate.[20] To meet the 60% goal the LID/NCDP provides a number of best practices that should be used by the developer, including the use of permeable pavement.[21] Permeable pavement is allowed for both parking and sidewalks,[22] with a specific recommendation for the use of permeable pavement for the construction of any parking spaces above the required minimum.[23] This portion of the ordinance allows the developer to increase the amount of land dedicated to parking, but does so in a way that will not increase to amount of run-off generated by those additional parking spaces. If a developer using these best management practices reaches the 60% goal, s/he is awarded a 5% discount on stormwater management fees.[24] This discount also scales up if a developer is able to meet a higher percentage of the stormwater volume that can be managed–up to a 30% discount.[25]

To view the provision see Sec. 35-210 Low Impact Development and Natural Channel Design Protocol (LID/NCDP).

Fairway, KS

Fairway has enacted ordinances that set mandatory permeable surface minimums for new development within the city.[26] The ordinance mandates a percentage of permeable and open space for Single Family Residential Districts, Business Districts, and Mixed Use Districts. For example, within the Single Family Residential Districts, any lot under 10,000 square feet must meet the 60% permeability standard.[27] This regulation also applies to lot sizes between 10,000 square feet and 30,000 in which the first 10,000 square feet must meet the 60% permeable requirement, and the remaining lot must meet 75% permeable requirement.[28] Finally, for lots over 30,000 square feet, the first 10,000 square feet must be 60% permeable, up to 30,000 square feet must meet the 75% permeability rate, and the remaining square footage must be 100% permeable.[29] The city also requires a mandatory minimum of green space within Mixed Space districts, and requires specific permeability and vegetation minimum for the space. [30]

To view the provision see Fairway, KS, Code of Ordinances Sec. 15-264 Zoning Districts.

Minneapolis, MN

Minneapolis enacted an ordinance in 2010 to revise its zoning code to allow pervious pavement for driveways.[31] Prior to 2010, most of the pervious pavement for driveways was not permitted or required a variance.[32] Under this ordinance, pervious pavement is permitted for driveways in all residential, commercial, and industrial districts subject to certain conditions and restrictions under the applicable provisions of the zoning chapter.[33] Namely, the ordinance requires that the pervious pavement or pervious pavement system be capable of carrying a wheel load of 4,000 pounds and installed per industry standards.[34] The ordinance also prohibits pervious pavement in areas used for the distribution of gasoline or other hazardous liquids that could be absorbed into the soil through the permeable pavement.[35] These conditions and restrictions ensure that the pervious pavement meets adequate safety and performance standards. The conditions and restrictions also protect the environment by ensuring that the soil is not exposed to hazardous liquids. In short, Minneapolis’s zoning ordinance for pervious pavement demonstrates a municipality’s solution to managing urban stormwater challenges by allowing permeable pavement for driveways.

To view this zoning provision, see Minneapolis, Minn., Zoning Code § 541.305.

ADDITIONAL EXAMPLES

Tybee Island, Ga., Land Development Code § 3-080(C)(5) (requiring new residential driveways and replacements of more than 50 percent of existing driveways be constructed of permeable materials designed to allow retention of at least the first one-inch of stormwater).

St. Petersburgh, Fla., Land Development Reg. § 16.40.090.3.3(6)(C) (allowing ribbon driveways as an acceptable alternative to standard driveways).

Duarte, CA, Development Code § 19.52.060 (C) (includes permeable pavement as a consideration in the sustainable development practices in the city).

DC Department of Energy & Environment, Permeable Surface Rebate Program (2017) (describes voluntary rebate program to create incentives for the use permeable pavement within the city with administration handled by a local nonprofit).

Waupaca County Shoreland Protection Ordinance, § 9.0 (establishes maximum allowable impervious coverage of residential, commercial, industrial or business land use within three hundred feet of the ordinary high-water mark).

CITATIONS

[1] Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, Pervious Pavement, 1 (2017).

[2] Benjamin O. Brattebo & Derek B. Booth, Long-term Stormwater Quantity and Quality Performance of Permeable Pavement Systems, 37 Water Research 4369, 4371 (2003); Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, supra note 1.

[3] Brattebo & Booth, supra note 2, at 4371; Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, supra note 1.

[4] Brattebo & Booth, supra note 2, at 4371; Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, supra note 1.

[5] Brattebo & Booth, supra note 2, at 4371; Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, supra note 1.

[6] Brattebo & Booth, supra note 2, at 4371; For additional information and photos see Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, supra note 1.

[7] Brattebo & Booth, supra note 2, at 4369.

[8] Andrew Kavarvonen, Politics of Urban Runoff: Nature, Technology and the Sustainable City 11 (2011).

[9] An Liu et al., Role of Rainfall and Catchment Characteristics on Urban Stormwater Quality, 2-3 (2015); Kavarvonen, supra note 8, at 11.

[10] Kavarvonen, supra note 8, at 18.

[11] An Liu, supra note 9, at 3.

[12] Id. at 4-5; Kavarvonen, supra note 8, at 13.

[13] Environmental Protection Agency, Energy Efficiency in Water and Wastewater Facilities, 1 (2013) https://perma.cc/3UYJ-5XX7.

[14] Los Angeles County, CA, Code of Ordinances § 22.44.1512.

[15] Id. at § 22.44.1340 (G).

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] San Antonio, TX, Code of Ordinances §§ 35-210 (b) (2) (A), (B).

[20] Id. at § 35-210 (b) (2) (B) (2).

[21] Id. at § 35-210 (j) (3).

[22] Id. at §§ 35-210 (f) (5), (6).

[23] Id. at § 35-210 (j) (1).

[24] Id. at § 35-210 (b) (2) (B) (2).

[25] Id. at Table 210-2

[26] Fairway, KS, Code of Ordinances §§15-264, 15-456.

[27] Id at Sec. 15-297.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] Id at Sec. 15-407.

[31] See Minneapolis, Minn., Zoning Code § 541.305 (2017).

[32] City of Minneapolis, Community Planning and Economic Development Planning Division Report Zoning Code Text Amendment 2 (2010), https://perma.cc/3MK5-US72.

[33] Minneapolis, Minn., Zoning Code §§ 541.300, 541.305 (2017).

[34] Minneapolis, Minn., Zoning Code § 541.305(a).

[35] Minneapolis, Minn., Zoning Code § 541.305(a)(4).

Please note, although the above cited and described ordinances have been enacted, each community should ensure that newly enacted ordinances are within local authority, have not been preempted, and are consistent with state comprehensive planning laws. Also, the effects described above are based on existing examples. Those effects may or may not be replicated elsewhere. Please contact us and let us know your experience.