A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of City Planning, Department of City Planning, University of Manitoba Winnipeg by Jonathan Hildebrand, Copyright © 2012 Jonathan Hildebrand

Note: Here at Urban Ark, a question that constantly confronts our planet is — what does re-indigenizing urban space entail and look like? This post aims to inform this inquiry.

Abstract

Indigenous planning continues to emerge globally, with increasing emphasis being placed on Indigenous autonomy and planning practices. Much of its theory, practice, and literature are often oriented toward rural settings, but in Canada, where more and more Aboriginal people continue to move to urban centres, questions of urban Indigenous planning and development are becoming more pertinent. By discussing an example of urban Indigenous planning – specifically the values and characteristics of the Neeginan project or vision for the North Main area of Downtown Winnipeg – this thesis aims to shed some light on urban Indigenous planning, as well as how it may differ from, and overlap with, other forms of planning and other types of spaces and built environments within the city. In doing so, it offers not only an assessment of Indigenous planning as it has been undertaken in a particular urban context. It also offers an assessment of how planning in general can continue to decolonize its practices as it learns to better support and relate to Indigenous priorities and planning approaches.

The analysis relies on interviews with people involved with Neeginan over the years, Neeginan-related planning documents, as well as City of Winnipeg planning documents, to examine three main issues: the distinct qualities of urban Indigenous planning in a multicultural context; the ways in which conventional Western planning processes, historically rooted in colonial structures and mindsets, have operated in relation to Aboriginal peoples in Winnipeg; and the ways in which these two issues – the flourishing of Indigenous planning and the decolonization of Western planning practices – might overlap and interact in a discussion of the Neeginan case

Chapter 1: Introduction

Topic Overview and Background

A review of the relevant literature reveals Indigenous planning as a planning approach rooted in Indigenous worldviews and cultures that also has something to offer to conventional Western planning practices. In this thesis I examine the Neeginan concept or vision for the North Main area of Winnipeg, Manitoba, in terms of planning processes, built form, and those of the city around it. Since the late 1960s, ‘Neeginan’ has connoted various plans and initiatives for and of the Indigenous community in the North Main area of Winnipeg’s Downtown. Through discussing Neeginan alongside City-led planning initiatives on North Main, I present an example of what Indigenous planning looks like in a specific urban context, as well as its relationship with that context. The thesis also addresses recent calls for a broadening of what is considered planning – moving beyond conventional ‘top-down’ models to include diverse groups.

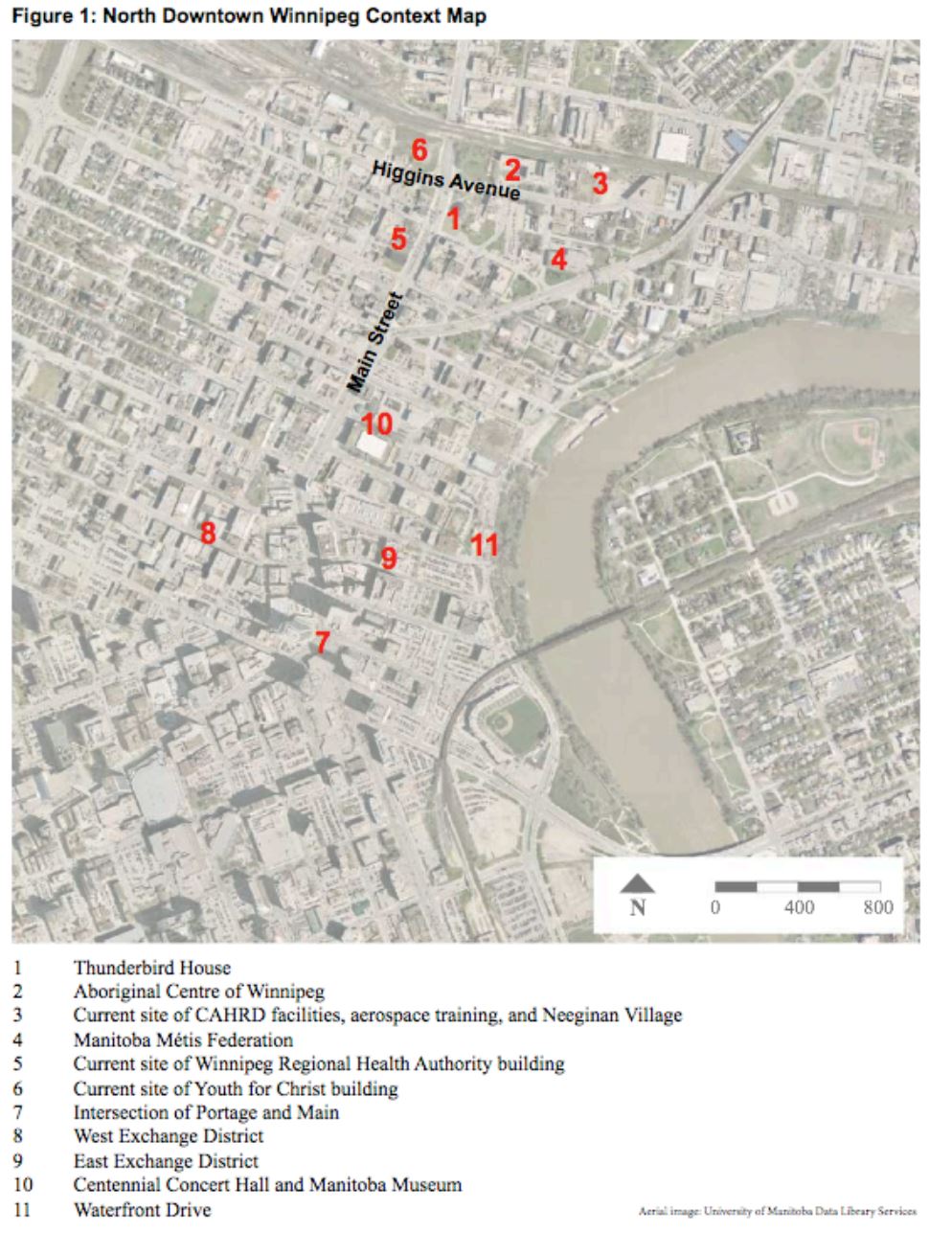

The field of research is the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, a very relevant context for this type of project as it has the largest number of Aboriginal residents of any city in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2006). Several blocks north of Portage and Main, Downtown Winnipeg’s commercial centre, the North Main area has a high concentration of Aboriginal peoples, with organizations such as the Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg, Neechi Foods Co-op, the Manitoba Métis Federation, and Thunderbird House all clustered in a relatively small area. Downtown was identified in the early 1970s as the locus for a possible “native people’s community or ‘village’” named Neeginan, a Cree word meaning “our place” (Damas & Smith, 1975, p. 10).

As people living on reserves began to migrate more and more to Canadian cities, including Winnipeg, in the 1950s and onward, they faced a variety of challenging circumstances. These challenges were seen by governments and administrators at the time as stemming from a “clash between the ‘traditional’ culture of First Nations people and the ‘modern’ culture of the city,” an issue that would need to be resolved through Aboriginal people changing “their personalities and cultures to fit into the city’s political and social order” (Hall, 2009, pp. 224-225). Aboriginal Winnipeggers, though, argued that “their cultures were not incompatible with urban living” and that the problems were rooted in lack of access to services of all kinds, and tied to a history of “systemic discrimination” (Hall, 2009, p. 225) that did not give them “immediate and real opportunities to participate fully in the new economies” of Canadian cities (Shead, 2011,p. 342).

Aboriginal community organizers in Winnipeg set about addressing these issues, and the 1975 Neeginan report and proposal (Damas & Smith) was very much a part of this. The area around Main Street and Higgins Avenue was to become a localized hub of Aboriginal social, economic, educational, and cultural activity, but it was not until much later that this vision would gain meaningful traction. In 1992, the Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg Incorporated purchased the former Canadian Pacific Railway station at the corner of Main and Higgins, retrofitting and redeveloping it with financial assistance from Canadian Heritage, Heritage Manitoba, and the Winnipeg Development Agreement (Shead, 2009, p. 345). The Centre now houses numerous Aboriginal organizations including the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre and the Centre for Aboriginal Human Resource Development (CAHRD), the latter of which includes the Aboriginal Community Campus, the Neeginan Institute of Applied Technology, and Kookum’s Place daycare. The Neeginan Village (a housing complex for CAHRD students), and the Aboriginal Aerospace Initiative (a program and facility training Aboriginal people for work in the Aerospace Industry) are also along Higgins Avenue, with future developments still in the works (Shead, 2009, p. 347). In the late 1990s, plans also began for the development of Thunderbird House, an architecturally striking cultural and spiritual centre just to the south of the Aboriginal Centre. Part of the original Neeginan vision, this facility includes a sweat lodge (distinctive in the context of an urban environment), and provides a space for numerous traditional ceremonies and gatherings of Aboriginal cultures on an inclusive basis. It has been offering the services and

guidance of Aboriginal Elders to Aboriginal people exiting institutions such as the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba – and also to the wider population – through the Elders’ services program (Community and Youth Solutions, 2011). Thunderbird House also opens its doors to the non-Aboriginal community, with its main rotunda area offering rental space for a wide range of business meetings, presentations, and other events.

While Thunderbird House and the Aboriginal Centre are not formally affiliated, they do represent major components of the overall Neeginan development and planning vision. This area of Winnipeg has also been the subject of various other types of developments, the 1967 centennial mega-project of the Centennial Concert Hall and Manitoba Museum being one example, the more recent Waterfront Drive redevelopment being another. The United Way, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, and Youth for Christ buildings are also recent examples. These, like the Aboriginal organizations mentioned above, have made their mark on Main Street. Historically, Downtown (Main Street included) was from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries a bustling commercial hub. Culturally it has been and continues to be home to a wide range of groups – not only Aboriginal and European, but also populations from Asian, African, and Middle-Eastern countries. Since its early days of commercial prominence, the area has experienced decline and neglect, and has developed a reputation in the city as a dangerous place. Its reputation, combined with subsequent attempts at revitalization and redevelopment (especially from the 1960s to the 1980s), as well as its evolution into an Aboriginal cultural centre, makes for a rich context in which to study multiple types of planning and development initiatives in a multicultural context (see Figure 1 for a map of

the area).

Research Questions and Objectives

This project is not a blow-by-blow history of Neeginan, nor is it an itemized rehashing of the various City-led development schemes for Downtown. Instead, it examines and analyzes the underlying visions and aspirations for planning and development spearheaded by Aboriginal groups as well as the City of Winnipeg in the area particularly around Main and Higgins. Through this approach, I intend to explore three main issues: firstly, since Indigenous planning is still emerging and growing as a series of processes and approaches to planning, I examine what these processes look like in an urban context.

Secondly, I explore the ways in which conventional Western planning processes, historically rooted in colonial structures and mindsets, have operated in relation to Aboriginal peoples in Winnipeg. In so doing, I recognize the need for these processes and the planners associated with them to decolonize, through self-examination of their own roles, and also through greater cross-cultural listening and learning from other

planning approaches (and as an emerging planner myself, I acknowledge my own role within these processes).

Finally, this project attempts to explore ways in which these two issues – the flourishing of Indigenous planning and the decolonization of Western planning practices – might overlap and interact in a discussion of the Neeginan case. The following research questions are intended to guide the research and analysis:

- What is Neeginan, and how has it evolved over time? What features have characterized in, and what values have informed it?

- What can an examination of Neeginan say about Indigenous planning within urban spaces consisting of diverse and multiple interests, stakeholders, and groups?

- How does Neeginan’s approach compare with non-Indigenous planning approaches and practices, particularly in comparison with City-led planning

initiatives for Winnipeg and North Main? - What implications might the results of this discussion have for planning theory and practice?

Personal Background, Biases, and Limitations

My interest in this topic stems from previous academic work as well as previous employment with urban Aboriginal groups and rural First Nations. My previous studies in History focused on processes of social and spatial marginalization and how these processes came into play in cross-cultural relationships in Canadian cities. Before attending planning school, I was employed in community work between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Winnipeg, where I also had the opportunity to learn and experience traditional teachings and ceremonies, through Aboriginal Elders and community organizers. More recently as a planning student, these interests have dovetailed with an interest in how planning affects the spaces and built form of cities, as well as the role of planning processes in relations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal groups in urban environments. As a planning student I was also exposed to the concept of Indigenous planning through coursework and though attending an international conference and field school on Indigenous planning in Chiapas, Mexico. All of these personal and academic factors led me to explore the topic of this thesis.

The limitations of this thesis include the fact that, as a Caucasian male with a Euro-Canadian background I am an outsider to urban Aboriginal communities in Winnipeg. In order to address this, my research takes a reflexive approach in which I am cognizant of my own position within the processes of research and analysis, and engaging this topic also as a learning (or ‘unlearning’) opportunity and part of my own personal process of decolonization. This was of particular importance in interviewing people for the thesis, and the ‘Research Methods’ section goes into more detail on this issue. Along the same lines, I am grateful that the interview participants for this project, all of whom are Aboriginal, were so gracious to me as an ‘outsider,’ offering helpful and insightful comments in formal interviews and informal conversations.

Another limitation to the thesis is the fact that only six people were interviewed, a relatively small number resulting from circumstances such as people’s availability and location (some people involved with Neeginan over the years had since moved from Manitoba). Some others from Neeginan’s earlier days are now deceased. Interviews were therefore examined alongside documents and reports. Also, no interviews were conducted with people associated with planning and development at the City over the years. This could be an area of future research for projects more focused on the functions of planning bureaucracies and practices in Winnipeg, and how these might relate to processes of marginalization. For this particular project, however, while the municipal city planning context was very important to the research, I wanted to focus also on the perspectives and voices within Indigenous planning and their relation to the city planning context.

Another issue the thesis does not discuss in detail is the presence of various Métis-led developments in downtown Winnipeg. Instead, it focuses more closely on the initiatives within Neeginan, which have been associated largely with First Nations groups. However, since Neeginan-affiliated programs and organizations, because of their urban focus, are geared toward First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people in Winnipeg, the term ‘Aboriginal’ is generally used throughout the thesis. I use the term ‘Indigenous’ in relation to Indigenous planning generally but use ‘Aboriginal’ when speaking of the Winnipeg context, as it is used more by community organizers in Winnipeg and is reflective of the complex issues of Indigenous identities and experiences in urban settings.

The complicated nature of cultural identity issues, particularly in the urban context raises the important point that Aboriginal cultures and worldviews are much more complex than a Caucasian Euro-Canadian graduate student can relay. While this project does touch on the depth and richness of Aboriginal traditional worldviews, it does so more in terms of land, space, and planning, specifically in terms of how land and space are conceptualized, and the worldviews informing such conceptualizations. I nevertheless do acknowledge that Aboriginal cultures and worldviews are much more diverse and far-reaching than the specific planning focus of this project, and recognize that they speak to more than only conceptualizations of land and space.

Outline of Chapters

The following chapter outlines in more detail the theoretical foundations of the thesis, reviewing the literature most relevant to how I approached the research. Two broad streams of literature are discussed. The first deals with the varied ways in which Indigenous planning has been discussed, theorized, and carried out in practice. The second deals with theorizations of space, particularly urban space, and spatial theories of and related to issues of Indigeneity and colonialism. Chapter Three details my research methodologies and the sources consulted for the research, as well as the ethical crosscultural issues accompanying this type of work. In Chapter Four I present and analyze the results of the research, and the final chapter summarizes this research and analysis by returning to my original research questions. Chapter Five also touches on some areas of future research as well as some potential implications of the conclusions reached in this thesis for future planning theory and practice.

To read the entire thesis please click here.