The artist and residential school survivor created vivid works that meld Denesuline iconography with modern and contemporary styles.

by Rhea Nayyar July 17, 2024.

Contemporary painter and Cold Lake First Nations resident Alex Janvier died on July 10 at age 89, as confirmed by his family, who shared the news on the artist’s Instagram account. Remembered for his vividly colorful paintings melding Indigenous Denesuline artistry with modern and contemporary styles, Janvier and his work are celebrated in museums and private collections across North America and internationally.

Janvier was born in 1935 on Treaty 6 territory in eastern Alberta to Mari Janvier, a Saulteaux (Ojibwa) woman, and Harry Janvier, the last hereditary chief of the Cold Lake First Nations before the federal government imposed elected officials. The artist, one of 10 siblings, spent much of his childhood learning the Dene language and Denesuline customs for how to live off the land up until age eight, when he was taken to the Roman Catholic-run Blue Quills Indian Residential School. Janvier has recounted the trauma he endured at the school over the years. In an interview with CBC News, he shared his experience of being loaded onto a cold truck with other children, forcibly stripped, and showered in a group before having their culturally significant braids cut off.

Disconnected from his family and culture for 10 years, Janvier embraced the therapeutic benefits of drawing and painting at the Blue Quills school, where he was provided with materials and art instruction. “I found a certain time of the week, you could escape from the whole outlay of controls,” he told Ottawa Morning‘s Hallie Cotnam in an interview. “And for about three hours, you’re in your own world, and that’s when I began to discover my ability to work on paper and beautiful colours — all kinds of colours.”

As a teenager at St. Thomas More College in Saskatchewan, Janvier was under the tutelage of University of Alberta professor Carlo Attenberg, who introduced the young artist to the work of Wassily Kandinsky and Joan Miró. By 1960, Janvier completed his Fine Arts education at the Alberta University of the Arts in Calgary, and taught briefly before committing his time entirely to painting. In 1968, he married Jacqueline Wolowski, with whom he went on to have six children. The couple remained together until his passing.

In the early ’70s, Janvier became part of a group called the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation (PNAI, but also informally called the Indigenous Group of Seven) with artists Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Ray, and Joseph Sanchez. The PNAI presented modern and Indigenous artwork to the mainstream Canadian art market, extracting it from the typical narrative of First Nations handicraft work. Not only did they exhibit and market their creative output as fine art, but they also promoted artmaking in Indigenous communities across Canada through educational opportunities and scholarships funded in part through their artwork sales.

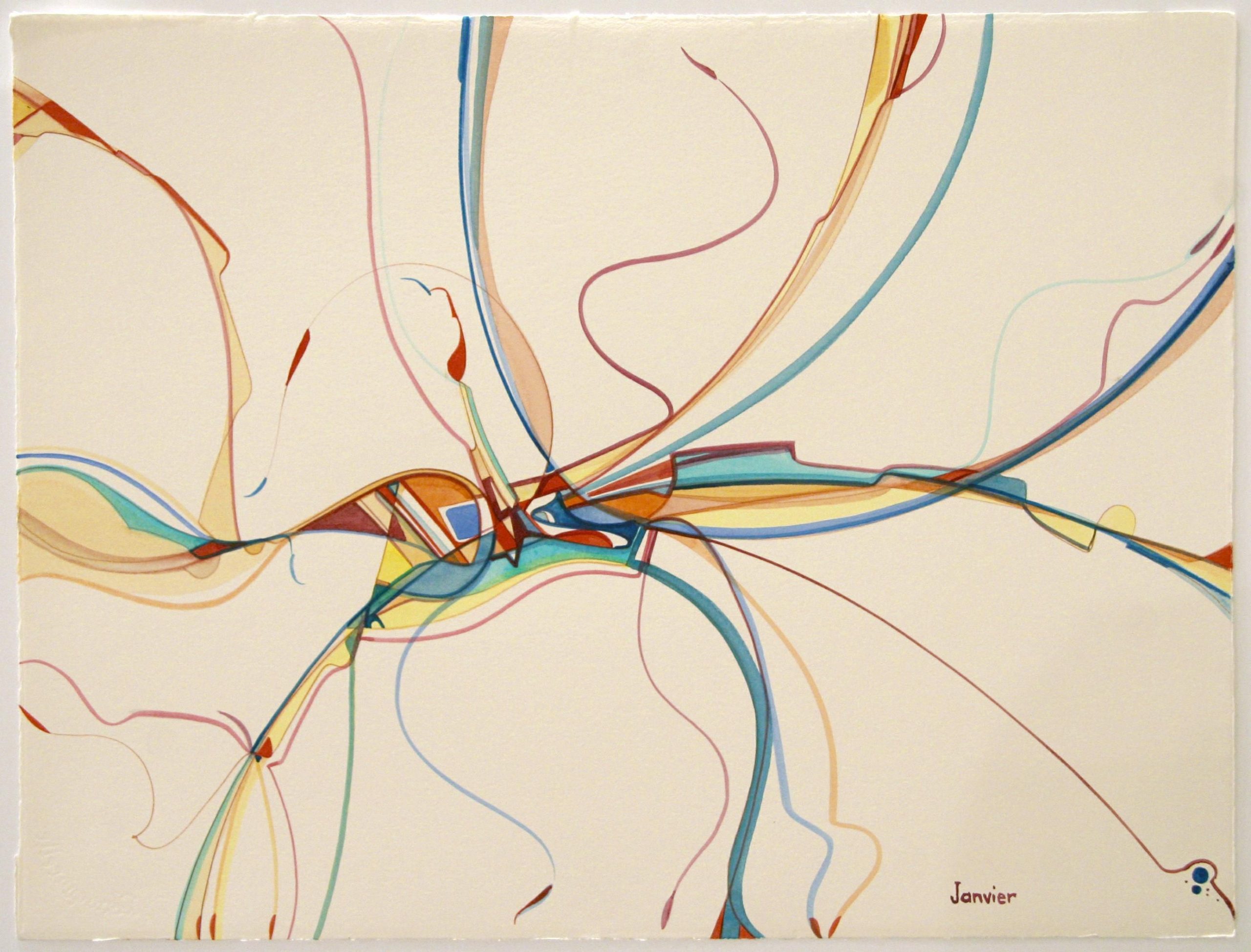

In his own work, Janvier is best known for his colorful abstractions combining Denesuline geocultural references with European Modernism. Ranging from bold, vivid acrylic compositions of flowing lines, organic shapes, and dotted patterns to shifting and bleeding sweeps of watercolor on paper, Janvier evoked the natural world, Denesuline cosmologies, and his familial relationships through his work for the last 70 years.

Janvier has been included in various group and solo exhibitions since 1950, with more specialized attention paid to his unique practice starting in the early 2000s. The artist and his family established the Janvier Gallery in 2003 and later moved it to Cold Lake First Nations land, where he maintained his studio practice, exhibited and sold his work, and featured the work of other Indigenous artists across Canada. In addition to multiple solo shows at Bearclaw Gallery and Canada House, Janvier had a retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 2016, and many of his public commissions remain on display throughout the country.

The artist is survived by his wife, Jacqueline; their six children; and 22 grandchildren, as well as countless friends and relatives.