A conversation between Ashley Minner (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina) and Dare Turner (Yurok Tribe of California)

April 18, 2022, Words: Ashley Minner , Dare Turner

Source: https://bmoreart.com/2022/04/native-american-visibility-and-the-baltimore-reservation.html

Think back to the last time you saw something related to Native Americans in Baltimore City. Maybe while flipping through the Department of Public Works calendar that arrived in mailboxes a couple of months ago, you noticed that Columbus Day has been officially changed to Indigenous People’s Day. Or perhaps you saw someone wearing a Native headdress as a Halloween costume. Or during Native American History Month, your kid learned about how the Natives helped the settlers make it through the winter. Based on all this data, one might draw the conclusion that Native presence in Baltimore is just part of a mythical historical past.

The artist and folklorist Ashley Minner wants you to know that Native heritage in Baltimore is vital and alive, continuing to this day. If you’ve been here long enough, you’ve probably driven by a historic site related to Native history in the city without even realizing it. Native American people have, in fact, always been present in what is now Baltimore; theirs is a dynamic story of migration, shifting demographics, and ongoing response to the intense pressures first ushered in by colonization.

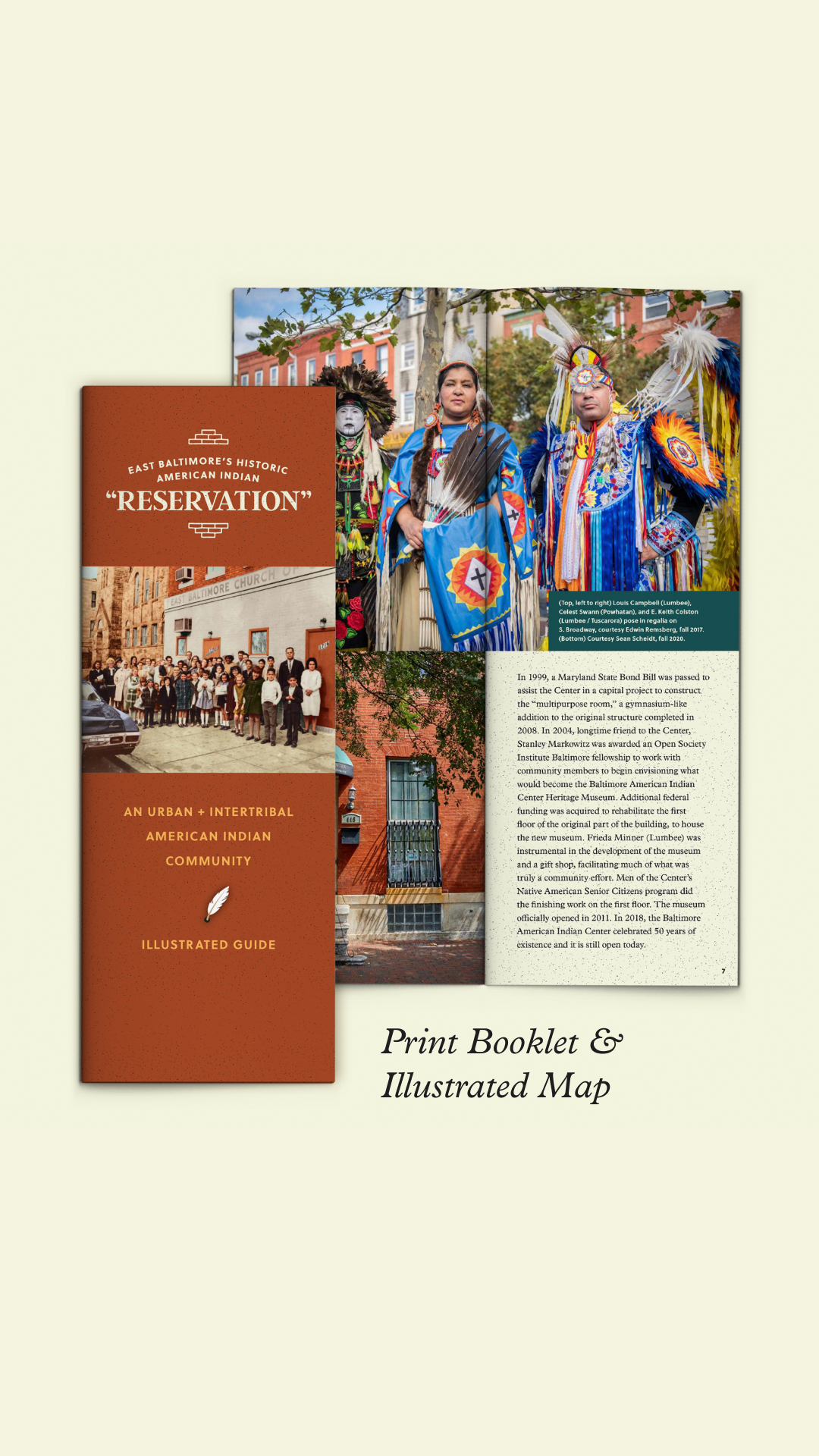

Minner’s recent multimedia project The Baltimore Reservation uncovers the often-overlooked history of the Native community’s presence in Baltimore, which peaked in the mid-20th century and endures today. Through a website, print map, iPhone app, and Android app, The Baltimore Reservation centers the Native community’s impact on our urban landscape and surfaces how “thousands of Lumbee Indians and members of other tribal nations migrated to Baltimore City, seeking jobs and a better quality of life.” The project aims to rectify the fact that many places in the city were at one time definably Native, but that history is no longer visible or recognized in public memory due to various interconnected forces such as gentrification, urban renewal, economic hardship, and upward mobility.

Minner’s project, which grew out of many years of deep research in archives and interviews with elders, humanizes Native history and tells the story of their role in the development of modern-day Baltimore. This dramatically departs from so much of Native history, which is written in a historicizing mode that erases modern-day Natives and renders urban Native populations invisible. According to popular understandings, the Native is not a person who lives but, rather, a friendly peaceful neighbor that fed your ancestors turkey, or an artifact of the violence of western expansion. In history books, Natives vanished into the slivers of wilderness afforded them or walked off to remote reservations somewhere out west. But Native Americans are still here. Some do live on reservations, but nearly three-quarters of Native Americans in the US live in urban areas like Baltimore, and have done so for a very long time.

The movement of Natives to cities was a result of economic, political, and racist forces. Novelist Tommy Orange, who is a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma and grew up in Oakland, CA, raised the issue in his book There There. “Getting us [Natives] to cities,” he writes, “was supposed to be the final, necessary step in our assimilation, absorption, erasure, completion of a five hundred year old genocidal campaign. But the city made us new, and we made it ours. We didn’t get lost amidst the sprawl of tall buildings, the stream of anonymous masses, the ceaseless din of traffic. We found each other, started up Indian Centers, brought out our families and powwows, our dances, our songs, our beadwork… We did not move to cities to die.”

Dare Turner: Ashley, does this excerpt from Tommy Orange’s book resonate with you?

Ashley Minner: It’s funny you should ask—I actually quoted part of this passage in my dissertation. Yes, this really resonates with me because it’s the story of our community here in Baltimore, too. And it supports my argument that the city itself has become part of our identity.

Can you tell me a little more about how so many members of the Lumbee Tribe came to this region and how you learned about this history?

The earliest evidence of a Lumbee in this city that I’ve found thus far is connected to Dr. Governor Worth Locklear, an 1893 graduate of Baltimore University Schools of Medicine who is credited as being the first Lumbee physician. He obviously came up here to get his education, which he could not get at home in North Carolina. My friend, Walker Elliott, mentions him among other Lumbee scholars who left the tribal homeland and infiltrated white colleges and universities across the south for the same reason. While researching my family history, I discovered that Dr. Locklear was my great-grandfather’s uncle. Whatever my great-grandfather’s reason was for coming in the 1940s, I believe he felt reassured that he could make a go of it here because he knew his uncle had before him. This is the way ethnic communities form in diaspora.

The Lumbee people’s tribal homeland is in North Carolina, so why did they come to Baltimore instead of a city closer to their ancestral land?

By the mid-20th century, many Lumbee families found themselves sharecropping in their tribal homeland, of which they had been dispossessed through the southern agricultural system. It was also the Jim Crow South, and in that region there was actually tri-racial segregation. It was a rough time. Lumbees migrated to a lot of different cities seeking jobs and a better quality of life. Some moved closer to home, to other places in North and South Carolina, while some went all the way up to Pennsylvania and even Michigan, but Maryland was the most popular destination. Literally thousands settled in Baltimore.

John Waters famously once declared, “I would never want to live anywhere but Baltimore. You can look far and wide, but you’ll never discover a stranger city with such extreme style. It’s as if every eccentric in the South decided to move north, ran out of gas in Baltimore, and decided to stay.” This statement rings true in sentiment, but I argue that most folks who came from further south did not arrive here by accident. Baltimore was often the destination for those coming from the Carolinas, Virginia, and West Virginia during the World Wars and post-war years, just as Chicago and Detroit were for those coming from Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Alabama. This accounts for at least part of the reason Baltimore is occasionally referred to as the “northernmost southern city.” Anthropologist John Gregory Peck wrote about Baltimore being an ideal landing place for the Lumbee because it is a southern city and because it was a stop on an express bus route coming directly from the homeland. He also notes that the particular area where Lumbee settled was “a ‘middle ground’ located between white and Black residential areas. And it was a place that had already accepted waves of immigrants from various world locales for hundreds of years.

The backbone of Minner’s project offers a window into the history of specific sites with rich histories related to the urban Native community. This history is shared with the public in a few ways: a physical guide designed by Julia Evins and Bob Cronan, a newly developed website crafted by Katie Lively replete with both contemporary photographs by Sean Scheidt and historic photographs, and a walking tour shared on the new app Guide to Indigenous Baltimore that was created in collaboration with Native scholar Dr. Elizabeth Rule (Chickasaw).

Let’s dig into the map piece of this project first. Mapping is a profoundly colonial activity. When we think of mapping Native history, we might look at treaties from early American history in which colonizers acquired land from Indigenous populations. An important example from our region is the treaty signed by the Susquehannock people that ceded a portion of northern Maryland’s Bay and a bunch of land, too. Public historian Emma Bilski’s research brought attention to this 1652 treaty and its statement that colonial Marylanders and the Susquehannock “doe promise and agree to walke together and Carry one towards another in all things as friends and to assist one another accordingly.” Unfortunately, like in countless other cases, the colonizers broke the conditions of the treaty with unprovoked violent attacks. That violence, in combination with relations with other nearby tribes and extensive white colonization, pushed the Susquehannock people out of the region and eventually resulted in the decimation of their tribe through more violence and disease. The storied history of Native people in this region that followed is hard to track because it is multi-layered and much of the historical record privileges the colonizers’ perspective. That privilege is surfaced both in history books and maps.

Often, western approaches to mapping and concepts of land ownership do not align with Indigenous understandings of the world. In the words of Ruben Pater in his new book CAPS LOCK, “to map is to conquer.” He writes, “If you took at most maps used today, we see the offspring of colonial mapping practices… [which] established a Eurocentric worldview….”

Ashley, what do you think about Ruben Pater’s assessment? Do you think mapping is connected to colonialism?

I think it’s a fair assessment and evidence of colonization is certainly baked into the map we made. I mean, the text is English and is, in most cases, intended to be read left to right, top to bottom; north is “up,” etc. We’ve documented only sites established after colonization began.

How do we reconcile the idea of mapping with the Native communities’ relocation to urban centers?

It’s good to remember that Lumbee people are settlers here, too. It’s also important to realize that Indian identity isn’t a thing that necessarily decreases over time, and with exposure to other cultures. For example, our people spoke English early on and we made it our own (see all the videos on Lumbee English on YouTube). We adapt. So in this case, we took some tools of the colonial society in which we live and wielded them to suit our needs.

When did you first think of mapping the urban Native history of Baltimore?

I guess I must have been thinking about it in the early 2000s because I found this old sketch. That thinking grew out of a desire to make our community visible because, through my own lived experience, I realized people don’t even know we’re here. Before I started to research in earnest—around 2018 or so—even I had no idea about half of the spaces we once owned and occupied.

Did this map need to change over time?

Well, yes. I mean, looking at my sketch now, which was obviously just a quick sketch, I can see that most of my landmarks aren’t exactly in the right place. And of course, nothing is to scale. The alley streets look like the street-streets… Interestingly, some things really stayed the same. From my notes, I can tell I was already wrestling with whether or not to map folks’ homes, and if so how, how to make the mapping process participatory, etc.

What does it mean to reclaim the activity of mapping?

For one thing, it means you have the power to decide what information is placed at the forefront and what information is made to recede into the background or is even left out. As people who have consistently been left out, this project is about publicly claiming power and ownership of our history and presence in this place. And this comes with responsibility. For example, Lumbees make up the majority of Indians in Baltimore but we aren’t the only Indians here. Members of other nations are present and also have history in the city, so I really tried to be inclusive and lift all of us up. I hope folks understand we have a diverse and intertribal community.

Tell us the importance of creating a print map in addition to the website and app. Who helped you create the map and what went into that process?

I am partial to print and that’s no secret, so I did want the paper map for myself, but I wanted it for the elders who collaborated with me even more. I felt they would be able to access the information most easily in this format and predicted they would proudly share copies with their friends and families. They’re doing that now! Bob Cronan designed the maps and created original, to-scale illustrations of ten of the buildings on “the reservation,” many of which no longer exist. He resurrected them from photos. Then Julia Evins worked her magic incorporating the map into the very beautiful guide she designed. It’s a functional art object. Julia pored over the guide with me for months and even oversaw the printing process to make sure it would be of the very highest quality. Here, I also need to give a shoutout to master-printer friend and fellow Dundalkian, Phil Civitarese, who liaised the entire production, led us through a press check, and even personally delivered the finished guides to my house.

Can you talk about your process of interviewing elders?

I have always loved my elders. I was raised with my grandparents close by, and while growing up I went to at least one of their houses every day. I miss them every day now. Since I was a teenager, I have been like an honorary member of the Native American Senior Citizens group of the Baltimore American Indian Center. They used to have half the building at 1633 E. Lombard Street and they would meet there for lunch and to hang out every Thursday. I was there as often as I could be. I never missed their fundraisers or parties or other outings. They are the best and funniest storytellers and they love me, too. The Indian Center sold their space in 2017, so they stopped meeting regularly for a few years. When I started researching our community history, the first thing I did was find some money to invite all of them to get together for lunch again and we had a great time. They stuck with me all the way and this project is as much theirs as it is mine. In fact, they now meet semi-regularly again, at the Boulevard Diner in Dundalk, and I want to say that’s in part due to all the meetings we had for this project.

Can you share some feedback you have gotten from elders in your community?

Sure! Linda Cox (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina): “Thank you so much… My heart is overwhelmed with joy. My mom would be so happy… Ashley, I thank you so much for having the vision and using all of our people to make them feel… they are special! We are here! We’re not going nowhere and our kids can be proud… If time stands, our kids will have something that they can actually be very, very proud of, and Ashley, we thank you for having the vision to put it together.”

Donald Locklear (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina): “Thank you for the brochures! You do not know all the memories that came with those photos.”

Kirby Hunt (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina): “Thank you for the reservation books. They are going to all my kids and my two brothers. Very good work on your part!”

Dan Nicholas (Munsee-Delaware): “They are beautiful. Thank you very much.”

New technologies allow us to tell stories in a dynamic way that has never been possible before. Your free app, Guide to Indigenous Baltimore, is a shining example of this. How did you first come up with the idea to collaborate with Dr. Elizabeth Rule to create an app for Baltimore?

Elizabeth and I were on a panel, along with Dr. Gabrielle Tayac (Piscataway), for American University in 2019. Elizabeth had just launched the Guide to Indigenous DC app, so she talked about that. I was in the middle of research to flesh out my walking tour of East Baltimore’s Historic American Indian “Reservation,” so I talked about that. Elizabeth mentioned wanting to expand her project to other cities and we both thought it would be really cool to have an app version of my tour. In 2021, I was awarded a fellowship from the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation to make it happen. Elizabeth provided the template and the technology; I provided the content. That’s how the Guide to Indigenous Baltimore became the second app of Elizabeth’s greater Guide to Indigenous Lands Project.

[Ed. Note: the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation is a major supporter of BmoreArt.]

How should people use the app? Do they need to be on-site or is this something that can be done remotely?

Folks can download the Guide to Indigenous Baltimore app from the App Store and Google Play. They can take the tour virtually, from anywhere, or follow along in person. Because we have included sites across the city, we don’t recommend physically walking to all of them, but invite folks to walk between sites on the historic “reservation” because they’re relatively close together. Between the aesthetic choices of our fabulous web designer, Katie Lively, and the gorgeous photographs of my longtime friend and collaborator, Sean Scheidt, I think virtual versions of the tour are incredibly rich and as immersive as can be. Yet there is no substitute for actually being in a place where you get the sounds and smells in addition to the sights, a better understanding of who is around today, and an opportunity to realize who you are, physically, in that landscape.

What voices are present in the app and website? How did you go about curating the content and crafting the narratives?

There are soooooooooo many voices present in the app and website. My sources range from the elders to other community members to scholarly texts to newspaper ads and articles and the list goes on. Deciding which locations to include and how much information to include about each one was certainly a curatorial process. My original scope covered just the historic neighborhood, from the foot of Broadway on up to about Orleans Street, west to maybe Bond Street, and east to Patterson Park Ave. And I was mostly interested in the heyday of “the reservation,” so the 1940s through about 1980. But I quickly realized how arbitrary some of these limitations were, so I broadened my frame of reference. Like, at one point, I was emailing every Maryland archeologist I know trying to get more information about the three Paleo-Indian sites that are/were within present-day Baltimore City limits… because, why not? If we’re talking about Native history, let’s start at (what we think is) the beginning.

Is there anything you wished you could add to the map but ultimately decided against?

I still struggle with the fact that almost no homes have been included, though I did include rental properties that were once owned by the Baltimore American Indian Center. If you think about it, the real “reservation” was where the people lived and, in some cases, still live. I’m still trying to figure that out. Also, I certainly didn’t want to publish any information that would embarrass anyone, so I took great care to avoid that. So far, so good.

How does the presentation of your research vary across the different deliverables—the website, the app, and the paper map?

The parameters of the forms the research took ultimately forced us to limit what could be included and to reckon with just how much information would actually be digestible by our audiences. The website has the most information, the app has slightly less, and the paper guide has the least. Each resource offers its own experience and invites folks to check out the others.

Who is your target audience?

The elders were my primary audience but ultimately all of these resources are intended to be accessible to the general public. Katie Lively guided us through the process of choosing a palette and fonts that would be both conceptually sound and most legible to visually impaired folks. Both the app and website have text-to-voice options and image descriptions, etc. An inclusive and accessible design approach was important to our whole team.

What do you hope your audience takes away from engaging with your research?

I hope the elders know that their lives are incredible and that their contributions are valued—that THEY, THEMSELVES, ARE VALUED. They endured a lot and worked hard to create what younger generations of our community enjoy and maybe sometimes take for granted. I hope the general public knows that there is a diverse, vibrant American Indian community in Baltimore that’s been here for a long time. We’re part of this place, too.

What is on the horizon for you? How can we learn more?

I started my job as Assistant Curator for History and Culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in September. I love it. Our team is working on a big proposal for a future exhibition which I hope might include some of the information from the Baltimore Reservation project. We’ll see. I also just turned in a book proposal based on this research and I’m confident I’ll have a contract for that soon. In the meantime, I’m finally back in the studio, mostly drawing so far. I missed making things with my hands. I have a short artist residency coming up at Azule. I’m excited about that. Folks can visit ashleyminnerart.com and subscribe to my newsletter for updates.

Ashley Minner’s upcoming events:

- Legacies: Maurice Berger and Fred Wilson April 19, 2022, 6:30–8 p.m. EST, UMBC Fine Arts Recital Hall and streamed live via YouTube

This program is a celebration of the life and work of Maurice Berger (1956–2020) upon the 20th anniversary of his curation of the exhibition Fred Wilson: Objects and Installations 1979 – 2000, and the 30th anniversary of Berger’s appointment as curator of the Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The program also celebrates the 30th anniversary of Fred Wilson’s groundbreaking installation Mining the Museum with The Contemporary Museum and the Maryland Historical Society. Curator George Ciscle will moderate an intergenerational panel with Fred Wilson, Lee Boot, Symmes Gardner, Christopher Kojzar, and Ashley Minner.

- Indigenous Community Archiving and Collective Memory April 26, 2022, 7 p.m. EST, presented by Special Collections of the Albin O. Kuhn Library at UMBC via WebEx

A conversation on community archiving projects within American Indian communities of Baltimore and Philadelphia. Addressing issues surrounding preservation, shared stewardship, and digitization of physical artifacts and audiovisual materials, this virtual event will underscore the importance of community collaboration and reflect upon ways archival research can contribute to collective memory. Speakers include Jessica Markey Locklear (doctoral student, Emory University), Siobhan Hagan (founding director, Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive), Tiffany Chavis (Consulting Archivist, UMBC), Ashley Minner (Assistant Curator for History and Culture, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian). Free and open to the public via WebEx. This program is supported by a Maryland Folklife Network Grant from the Maryland State Arts Council. For more information, visit mdfolklife.org.

*****