By Stephanie Firestone and Miranda Wilson

Source:

https://www.aarpinternational.org/file%20library/build%20equity/aarp-indigenousurbanplanning-casestudy-230808-final.pdf

Needs/Challenges

At the heart of Indigenous culture are core values that include a reverence for elders and the perspective of multiple generations informing communal decision-making. These values undergird an international movement emerging in the late twentieth century to incorporate Indigenous knowledge

and cultural values into the planning, development, and design of the built environment in urban spaces, where the majority of Indigenous peoples now live and work. A 2022 Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur stresses the importance of having older persons who live in urban areas,

among a few key Indigenous subgroups, participate in decision-making related to urban planning and public life. This case study underscores the significant role of elders and the importance of a “sevengeneration” perspective, in order to holistically represent the community’s values, beliefs, history, and practices in future planning and design. It also illustrates some successful global innovations that built environment professionals can replicate in urban areas to ensure that cities where Indigenous peoples live reflect their specific social and cultural needs.

Indigenous peoples1 comprise distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties—“since time immemorial”—to the lands where they live or from which they have been displaced.2 There are approximately 5,000 distinct Indigenous ethnic groups worldwide, making up an estimated 95 percent of the world’s cultural diversity.

Largely because their remote locations limit access to economic opportunities, many Indigenous peoples have had to move from their communities to more urban areas. Consequently, in countries with the largest Indigenous populations, most of them no longer live in rural reservation/reserve spaces. In the United States, at least 67 percent are urbanites, in New Zealand, 84 percent have moved to urban areas, and Australia is close behind at 79 percent. In Canada, 44.3 percent now call urban areas home, though research suggests the number of Indigenous people living in cities may be more than twice what Census counts indicate.

These large Indigenous populations often reside in the marginalized sections of urban areas that have less access to the economic and formal infrastructure of the city. Because of this lack of opportunity, Indigenous peoples account for a disproportionate portion of the world’s extremely poor—at 19 percent—though they make up only some 6.2 percent of the population.

Given the displacement from their communities and their poverty, as Indigenous urbanites age, they often encounter significant barriers to accessing adequate health care, services, and housing. For example, in the United States, 70 percent of older American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) who are living in urban areas are often unable to access tribal services and must rely on Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs) for affordable and culturally appropriate services and care.3

Urban health services, however, make up just one percent of the budget of the U.S. Indian Health Service (IHS). These inequities faced by Indigenous peoples build throughout the life course; indeed, estimates of life expectancy for Indigenous peoples are up to 20 years lower than that of non-Indigenous peoples.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous peoples, with Article 21 stipulating the needs of Indigenous elders as the first among a few groups. The 2022 UN Special Rapporteur report makes it very clear that Indigenous peoples’ rights and cultural needs are not effectively addressed by public policies or urban planning. However, there is limited data on these needs. According to Collette Adamsen, PhD, Director of the National Resource Center on Native American Aging (NRCNAA), “If there is no data to justify the needs, then urban Native elders are left out of the conversation.” The NRCNAA, with support from AARP, recently conducted the first-ever Native Urban Elder Needs Assessment Survey (NUENAS), a culturally respectful set of questions fielded through a coalition of various service organizations and tribal entities. More resources such as these are critical to providing important information for planners and policymakers regarding the unique needs of urban Native elders in the United States and other countries.

Innovations

Intergenerational Connections to the Land

Though it is estimated that lands Indigenous peoples In interviews for this case study, experts emphasized the inhabited, roamed, and/or stewarded since time immemorial importance of engaging Indigenous elders, who hold a make up at least 32 percent of the earth’s landmass, only critical perspective on connecting with the land over a 10 percent of the world’s land is legally owned by Indigenous peoples, and most of these lands are in remote on reservation land, it is increasingly more challenging for elders to transfer this responsibility to their children. areas. Some Indigenous communities are succeeding in reattaining land rights, for example after decades-long legal battles three First Nations (groups of Indigenous peoples in Canada) have acquired vast tracts of land in Vancouver.

Control of lands is not merely a territorial question, as Indigenous peoples’ histories, cultures, religions, livelihoods, and spiritual well-being are inextricably linked to the land they traditionally inhabit. As such, sustainability of the land is a fundamental value among Indigenous communities. As Ted Jojola, PhD, Director of the Indigenous Design and and Planning Institute at the University of New Mexico, points out, “The right of inheritance obligates an individual to protect and pass on what they inherited at birth to their children.”

In interviews for this case study, experts emphasized the importance of engaging Indigenous elders, who a critical perspective on connecting with the land over lifetime. Yet, with fewer Indigenous young people living on reservation land, it is increasingly more challenging elders to this responsibility to their children.

Residential and commercial developments considered in this case study illustrate one important way in which culturally appropriate design can help facilitate this intergenerational engagement—through medicinal and food gardens that reflect Indigenous knowledge of native plants and botany. James Bergahan, Senior Lecturer in Māori Designed Environments at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, notes that Māori community gardens (or are “a space to grow food, but more importantly a space for maara ka) are “a space to grow food, but more importantly a space for intergenerational knowledge transfer” around ethnobotany, history, and land-based teachings. This deep connection respect for the land and future generations may explain why 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is on lands held by Indigenous peoples.

Culturally Relevant and Intergenerational Planning Practices

Intergenerational cultural education and the role of elders as culture carriers are core values among Indigenous communities. According to Janeen Comenote, Founding Executive Director of the National Urban Indian Family Coalition in Seattle, “If and where Native organizations can integrate intergenerational work, they do so.”4 However, the engagement of older adults as an instrument for a culturally responsive and value-based approach to Indigenous community development and planning is quite recent. Non-Indigenous city planners typically lead community efforts that envision five or 10 years ahead (and sometimes longer), but this still does not include the dimension of how people evolve over their lifetimes. And it rarely recognizes the importance of sustaining intergenerational engagement.

Distinct from this short-term approach, many Indigenous communities adhere to a unique “seven-generation planning model,” according to the experts interviewed for this case study. Community members are asked to imagine themselves as the middle generation, with their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents preceding them, and their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren after, so each of these voices is represented. Dr. Jojola says, “The spaces that are created harbor the custodians to human advancement.” The planning task is to develop a vision that is informed by the past and compelling enough that those who inherit it will want to continue the work, acknowledging that those who started it may not be able to see it through.

A variety of government and community actions are acting to bring these voices to planning tables. In the State of Queensland, Australia, the Planning Act 2016 requires the land use and environmental planning system to value, protect, and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples’ traditional knowledge, culture, and traditions as reflected by their elders, and the government-issued corresponding guidance materials on land-use planning for local governments and planners. The state also worked with the Planning Institute of Australia to design a course to provide planning professionals with an understanding of how to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait people’s interests in plan-making processes.5 The Canadian Institute of Planners developed a policy on Planning Practice and Reconciliation, which seeks to create a future where “planners build relationships with Indigenous peoples based on mutual respect, trust, and dialogue,” prioritizing a diversity of community voices, including those of elders. In Vancouver, the City Council issued 79 calls to action in 2022 that include prioritizing access to cultural sites, developing affordable and First-Nations-owned housing, and the inclusion of local First Nations representatives on city and regional boards.

Incorporating Indigenous Elements in Design

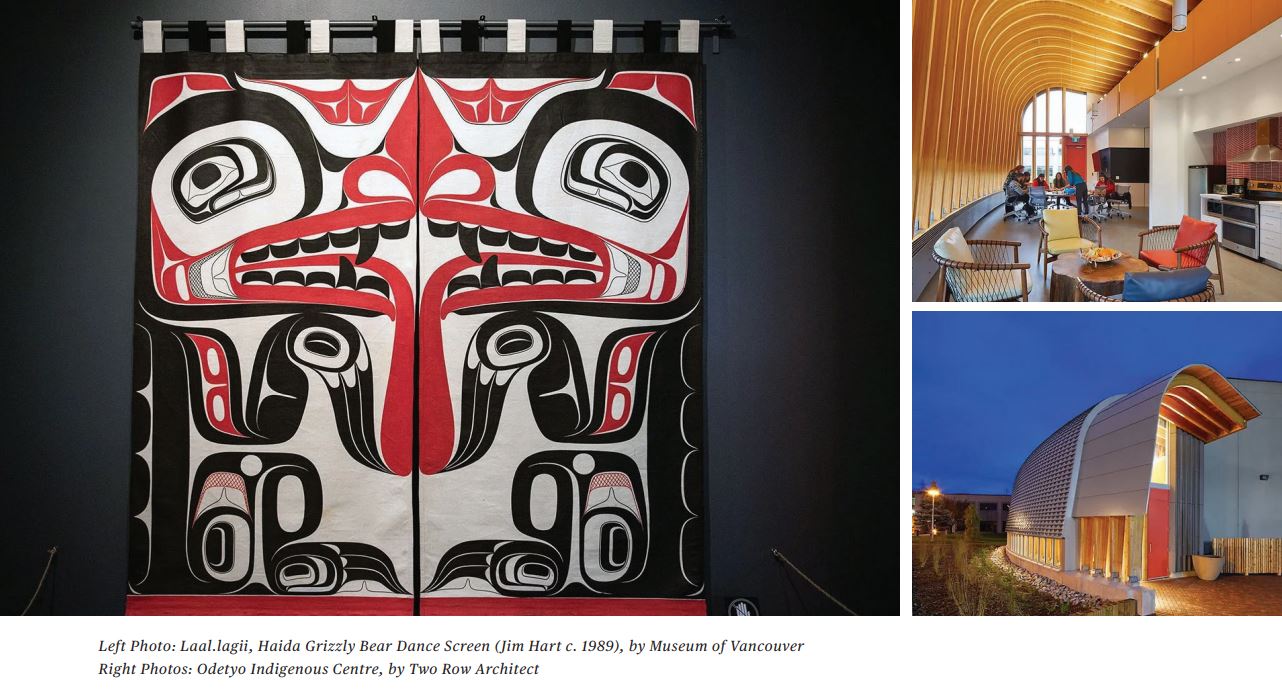

Whereas mainstream architecture tends to evaluate buildings on elements such as style, function, and form, Indigenous design is based on cultural meaning derived from older generations, according to Dr. Jojola. “Indigenous motifs are neither random nor simply decorative,” he says. Instead, they relate to cultural symbols that are integral to representing a worldview of Indigenous peoples that tribal elders seek to preserve.

Indigenous design also acknowledges the external world in a variety of ways. Matthew Hickey, a Partner at Two Row, an Indigenous-owned architecture firm in Canada, stresses that, “Indigenous design is not about the representation of people per se, but the representation of values and thousands of years of knowledge.” He suggested that this design approach helps older people, in particular, to cope and adapt to the challenges of outside influences alongside their traditions and values. Examples of Indigenous urban design can be found in various regions around the world. In Canada, the City of Vancouver collaborated with Indigenous elders and other community members to incorporate Indigenous design elements into public spaces, including Indigenous art, totems, and traditional place names. In the City of Toronto, Indigenous design principles are part of a reparative program that seeks to acknowledge Indigenous peoples through public art, naming of places, and engagement in policies.

Cities like Auckland and Wellington have embraced New Zealand’s indigenous Polynesian populations, the Māori,6 by employing Māori design principles and integrating Māori artwork, language, and cultural practices into urban landscapes. In 2017, the Auckland Council adopted the Te Aranga Māori Design Principles, which reflect core Māori cultural values, into the Auckland Design Manual (ADM), a resource that provides practical guidance for incorporating traditional Māori principles, knowledge, and culture into the contemporary built environment. The ADM includes guidance on Universal Design that accommodates a variety of abilities and ages across the lifespan—in housing, cafés and restaurants, play spaces, and more.

Housing Indigenous Older Adults

In the U.S., the National Urban Indian Family Coalition conducted a series of roundtables nearly a decade ago to determine the communities’ needs and priorities. Though they found housing to be among the top three issues, it has largely not been adopted as a focal area. A variety of needs and practices must inform this exploration.

First, the lack of affordable urban housing for older and younger Indigenous urbanites alike has led to an increase in homelessness. In fact, Indigenous peoples living in major urban areas experience homelessness at a disproportionate rate compared to non-Indigenous people. In Canada, for example, urban Indigenous peoples are eight times more likely to experience houselessness. Additionally, young First Nations women with children and older populations are most vulnerable to experiencing violence and thus are at greater risk of homelessness. These numbers do not even account for waht is termed “hidden homelessness,” or people who temporarily live with friends, relatives, or even strangers without any guarantee of continued residency or immediate prospects for accessing permanent housing.

Another important consideration is the proclivity for living intergenerationally. According to the 2023 NUENAS survey, nearly 60 percent of older Indigenous urbanites currently live with other family members. When asked how many individuals reside in their households, the numbers ranged from one to as high as twenty-four. A Canadian guide points to the need for elders, spiritual leaders, and flexible resources to keep families together, grounded in housing and healing. Such insights emphasize the need for a focus on appropriate multigenerational housing and support.

When living with family is no longer feasible and older people move into long-term care facilities, they are often located at the physical margins of communities where land is less expensive. This approach frequently exacerbates the marginalization of older adults from the rest of society.

In the case of Indigenous older people, it contradicts their core cultural value of living in a community among older and younger generations. Older Indigenous peoples, who are often taken from reservations to be cared for at mainstream institutions in urban areas when the tribes can no longer

support their care, may also have a heightened distrust of these long-term care systems. Institutions can work to overcome this resistance by incorporating elements that help preserve Indigenous culture and community. These might include adding cultural aesthetic and heritage elements to the physical design of the long-term care facilities, incorporating space for family gatherings and traditional ceremonies, and hiring staff that understand Indigenous culture, values, and attitudes.

The Māori community developed a toolkit for Kaumātua (tribal elder) housing to promote culture-centered, quality Kaumātua community and housing that reinforces “Kaumātua autonomy and self-actualization.” The toolkit calls for partnering with Kaumātua to co-design and co-create culture-centered, age-friendly housing, spaces, and facilities where Kaumātua have a sense of community. It advocates for nurturing strong, Kaumātua-centered tenancy relationships, including assessing the compatibility of residents and fostering belonging, ownership, and leadership in the community. It prioritizes monitoring and accommodating the changing needs of residents over time, which includes supporting the people who provide health care and other services for daily living and enabling them to stay over if needed. Importantly, the principles include ensuring Kaumātua can obtain resources to support them through these changes, so they can maintain self-determination and independence.

A Financial Commitment to Funding Māori Housing in New Zealand

New Zealand’s commitment to funding both small-scale Māori housing projects and larger developments in recent years is one that other countries should use as a roadmap when it comes to creating vibrant communities for their Indigenous populations. In New Zealand, homeownership

rates fell by nearly 10 percent between 1990 and 2013, with rates remaining static thereafter through 2018. The decline in homeownership occurred unevenly, with Pacific peoples and Māori less likely to own their home or hold it in a family trust than other ethnic groups. A 2018 survey in Auckland found that Māori made up 43 percent of people experiencing homelessness; the rates of severe housing deprivation among the Pacific peoples and

Māori communities were between four and six times the European rate.

In an attempt to rectify this issue, New Zealand launched a national inquiry in 2019 that focused on the intergenerational impacts from years of insufficient response to Māori housing issues, including the lack of new housing supply, the poor quality of existing housing, and the unaffordability for Māori to rent or own their own home. In response, the government released the National Māori Housing Strategy (MAIHI Ka Ora), which includes the Whai Kāinga Whai Oranga initiative. Jointly administered with Te Puni Kōkiri (Ministry of Māori Development), this is a four-year, $730 million commitment to fund both small-scale Māori housing projects and larger developments. The projects range from repairing existing homes to building new ones that are culturally appropriate. The government also abolished single-family zoning in major New Zealand cities in 2021, allowing property owners to build up to three housing units to a height of three stories and to cover 50 percent of what were once single-family lots.

These multiple housing lots are important because Māori tradition prioritizes living in multi-generational, family-based kāinga (villages) or pā. Traditionally they slept in rectangular wharepuni (communal sleeping houses). Other communal buildings included pātaka (storehouses), kāuta (cooking houses) and wharenui (meeting houses). Often the Māori accommodate more household members than the general population primarily for two reasons: their larger whānau (extended family) size; and strong values around manaakitanga (hospitality), which include welcoming and accommodating extended whānau and other visitors to one’s home on a regular and frequent basis for short periods, or receiving other whānau members such as parents and grandparents on a more permanent basis.

These longstanding cultural housing preferences are influencing modern Māori housing developments, including both family homes and “retirement housing.” The Moa Crescent Kaumātua Village in Hamilton, New Zealand was designed to replicate the concept of an urban papakāinga (or Māori housing on ancestral land). The Moa Crescent offers 14 affordable units, housing 19 residents aged 60 and over in a “village” that promotes communal living through shared spaces, including a garden. Moa Crescent is supported by the Rauawaawa Kaumātua Charitable Trust, which provides “wrap-around” health and social services to ensure Mao Crescent residents can age in place, regardless of ability.

These government initiatives, particularly those that unlock financing, are critical to honoring the unique cultural characteristics of Māori housing. The Auckland Design Manual includes a Māori Housing Hub to advocate for homes and housing designed to acknowledge and respond to the needs and aspirations of Māori communities. The Hub includes a Design Matrix which identifies housing-relevant Māori values and translates these values into built environment principles and objectives for designers.

Four Model Developments for Indigenous Peoples

An increasing number of housing and community developments are establishing partnerships between the government and Indigenous peoples in urban areas and serve as examples for built environment professionals. Here, we shine a spotlight on four from the U.S. and Canada, each of which has a slightly different mission.

AFFORDABLE INTERGENERATIONAL HOUSING IN PORTLAND, OR

It serves as a site for the Chief Seattle Club to provide food, health care, legal services, Native art job training, and cultural community-building.

The NAYA Family Center in Portland, Oregon, is at the leading edge of integrating Indigenous elders into all of their work, as all decisions are run through a robust Portland Youth and Elders Council (PYEC). The Council was initially formed to help reduce homelessness and, more recently, has become vocal about the need for intergenerational housing, leading to the development of Generations, an affordable forty-unit intentional community. PYEC also engages community members across the generations in constructive discourse, healthy debates, and civic action around a variety of needs, so they can take an active role in affecting social change and shaping their future. A young participant at a recent meeting expressed feeling very supported when the elders listened to their ideas. Then the elders told them about the long-existing history of engagement, and they said, “It was powerful. They built the path I walk on. It was a humbling and learning moment for me.”

TRANSITIONAL AND PERMANENT HOUSING IN SEATTLE, WA

In Seattle, Indigenous peoples make up 15 percent of the population experiencing homelessness and are seven times more likely than white people to be living in homelessness. Chief Seattle Club, a non-profit dedicated to supporting American Indian and Alaska Native peoples, has developed both transitional and permanent housing opportunities for Indigenous people experiencing homelessness. A variety of studio apartment developments are either complete or underway, including permanent supportive housing for elders. One development, ʔálʔal, which means “home” in Lushootseed (the language of the Coast Salish people in the Seattle area) reflects the Indigenous culture, and the building design establishes a community beyond housing. It serves as a site for the Chief Seattle Club to provide food, health care, legal services, Native art job training, and cultural community-building.

AN HISTORIC HOUSING DEVELOPMENT IN VANCOUVER

Senakw is a Squamish-led housing development based in Vancouver that seeks to address the city’s housing crisis while recognizing the site’s historic roots and representing the largest net zero carbon residential project and largest First Nations economic development project in Canada. The 11-tower, 6,000-unit residential project is located on 11 acres of reserve land across English Bay from downtown Vancouver.7 The development’s design is inspired by traditional oral storytelling and the values of the Squamish Nation. Their deep embrace of nature—the mountains, forest, and water, and their craftwork traditions of carving and weaving informed two distinct building typologies whose paths converge, “endorsing an urban dialogue with a broader vision of reconciliation.”

THE AMERICAN INDIAN CULTURAL CORRIDOR REVITALIZATION IN MINNEAPOLIS

The American Indian Cultural Corridor is a revitalization effort located in the traditional heart of Minneapolis’ American Indian community in the Phillips Neighborhood. The eight-block stretch of Franklin Avenue has a highly visible and concentrated set of Indigenous community buildings, family housing, various tribal offices, All My Relations Arts Gallery, Four Sisters Farmers Market, the American Indian Industrial Opportunities Center, the Indian Health Board, and the American Indian Center.

Founded in 1975, the American Indian Center is among the oldest in the United States. It provides educational and social services to more than 10,000 members of the community each year, including several programs for older people such as congregate dining, transportation, fitness activities, nutrition education, and cooking classes. The Center recently broke ground on a $32.5 million renovation and expansion designed for accessibility, with entrances and ground-floor activities closer to Franklin Avenue, including a new circular entrance intended to serve as a ceremonial gathering space. Among the first housing developments sponsored by U.S. Indigenous tribes, the Mino-Bimaadiziwin (“the good life” in Ojibwe) Apartments will serve as a home and community for 110 Indigenous families and individuals at Cedar and Franklin. The complex also includes a mental health and wellness clinic, supportive services, and a childcare center.

Replicability

As built environment professionals—and the policies, plans, and developments they promote—increasingly seek to reduce disparities among the urban Indigenous peoples who reside in their communities, this work must consider the large number of older people that increasingly reside in urban areas and should be informed by Indigenous history, knowledge, and culture. The primary way to do so is via consultation throughout the planning and design process. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)8 recognizes Indigenous peoples’ right to free, prior, and informed consent before undertaking a project that affects their right to land, territory, and resources. UNDRIP also describes the right of Indigenous peoples to maintain, protect, and develop past, present, and future manifestations of their culture, including designs and traditional knowledge.9

Indigenous elders should play a key role in this consultation process. As their community’s repository for cultural, land-based, and philosophical knowledge, medicinal practices, and languages, elders are often best equipped to convene their communities for these consultation processes. Elders are steeped in a relationship-building tradition, and Indigenous planners interviewed see this as the type of consultation that must take place. Hickey cautions designers that consultation is not a box to be checked or a static process.

He indicates that “while Western planning is based on milestones, we often run parallel processes” that ensure sensitivity and flexibility to relationship

issues throughout the planning process. This continuity of communication over time is critical to trust-building.

Furthermore, these experts instruct built environment professionals to consider the natural heritage in the specific site where they are working—both the place and its people. For example, when planners address heritage requirements of a place, this often refers to a time when settlers arrived; it is thus imperative to start with the question, “Whose heritage?” Indigenous planners say their people question the contemporary practice of “placemaking,” saying, “Our places are already made.” Alternatively, they promulgate the practice of “walking the land” with its elders and the idea of “place-knowing.”10 This approach advises planners that by inheriting these places, those who currently reside in them have a responsibility to the past and the future that goes beyond placemaking for themselves. Through focused interventions and culturally appropriate planning and design that rely on Indigenous elder knowledge, built environment professionals can increasingly meet the needs of local Indigenous communities as they age—creating spaces that reflect their identity, culture, history, and aspirations.

Notes

1 The United Nations defines Indigenous peoples as inheritors and practitioners of unique cultures and ways of relating to people and the environment that have retained social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live.

2 In law, time immemorial denotes “a period of time beyond which legal memory cannot go,” and “time out of mind.” It’s often used in judicial discussions of indigenous property rights. (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues)

3 In the U.S., there are approximately 41 UIOs, which operate 71 facilities in 22 states.

4 Interview with Janeen Comenote, October 2023.

5 It is important to note, however, that this Act fails to place specific consultation requirements on planners.

6 Māori people make up approximately 17 percent of New Zealand’s national population.

7 This land was expropriated in the late 19th/early 20th century and later returned to the Squamish Nation.

8 Unlike UNDRIP, the International Labour Organization (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal People’s Convention is a binding treaty that guarantees the rights of indigenous peoples. The convention has only been ratified by 24 countries, including most South and Central American countries. The U.S., New Zealand, Australia, and Canada are not party to the treaty. Article 7 of the Treaty explicitly deals with the right of indigenous peoples “to decide their own priorities for the process of development as it affects their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and the lands they occupy or otherwise use, and to exercise control, to the extent possible, over their own economic, social and cultural development.”

9 While this document establishes consultation and consent as a basis for built environment professionals working with Indigenous peoples and knowledge, it is a legally non-binding document and lacks specific guidelines for design practitioners.

10 Interview with Dr. Jojola, July 2023.