Source: https://www.pbssocal.org/news-community/how-japanese-american-incarceration-was-entangled-with-indigenous-dispossession

By Hana Maruyama August 18, 2022

Growing up, every elder I met seemed to have stories of collecting arrowheads — regardless of which camp they were sent to.

I also knew that my grandfather and his family had been incarcerated on Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) land.

My great-uncle had completed his Military Intelligence Service training at Fort Snelling, a former Dakota concentration camp located next to Bdote, a Dakota creation site.

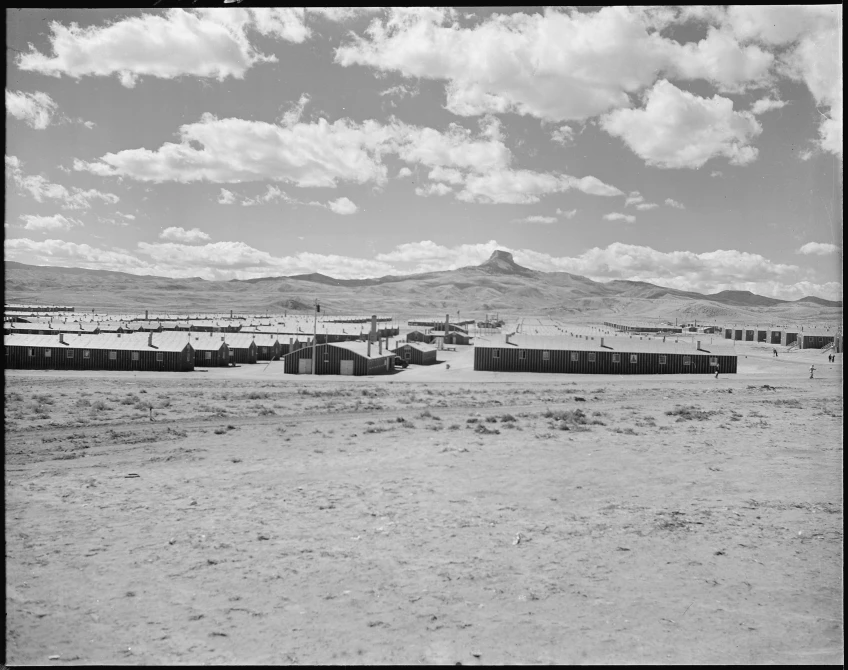

I was still thinking of these as a curious and unrelated coincidences when, in 2012, I got a job working for the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. The organization runs a museum commemorating the history of 14,000 people of Japanese ancestry who, like my paternal grandmother and her family, were incarcerated there during World War II.

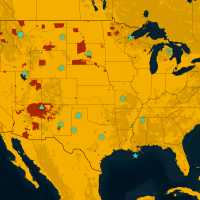

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/17a371627c7e4f9ca018c72580b93deb/

View in Fullscreen WindowThis project was created as a partnership between KCET and Ann Kaneko. Ann is the director/producer of Manzanar, Diverted: When Water Becomes Dust, a feature documentary about water and forced removals in Payahuunadü/Owens Valley. | U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs, 2018; Library of Congress, 2019; Densho Encyclopedia, 2020

I was surprised to learn that 50 years before the U.S. forced Japanese Americans into this American concentration camp in Wyoming, it wrapped up a decades-long effort pushing Apsáalooke (Crow) out of the area. It struck me that the Heart Mountain’s histories of governmental removal extended beyond my community. And I wondered why the U.S. government had gone to such lengths to remove the Apsáalooke, only to leave the site empty for 50 years.

Increasingly, I started to feel that these stories had to be connected — I just couldn’t quite puzzle out how.

Land Seizure and Broken Promises

Back in 1942, the GRIC Council refused to sign a lease with the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which would allow the use of their land to incarcerate those of Japanese ancestry. But construction had already begun when they were consulted in April. The GRIC conceded six months later, well after Japanese Americans first arrived on the reservation — when the WRA and Office of Indian Affairs threatened to withhold desperately-needed rental income.

The Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) promised the Council that incarcerees would develop the land and build infrastructure before the WRA returned it to the GRIC. After the war, however, the WRA sold off what buildings and materials it could, bulldozed the rest, and left mostly unusable rubble in its wake — a far cry from the promise of “improved” land.

Over the next few years, I collected more of these fragments: Leupp, an isolation center designated for Japanese American “troublemakers” in 1943, was set up in an American Indian boarding school on Navajo Nation land that had closed less than a year prior.

Poston was built on Mohave and Nüwüwü (Chemehuevi) land, against the wishes of the Colorado River Indian Community (CRIC) Council. Its approach reinvigorated lingering fears: “that feeling,” as Agnes Savilla (Mohave) put it in a 1978 oral history, “that whatever you own, and whatever you have, you’re at the mercy of the government; because they can take this away, and they can do that.” In fall 1945, the OIA again failed to consult the CRIC Council when it placed Hopi and Diné (Navajo) in barracks at Poston scarcely vacated by Japanese American incarcerees.

I initially thought these overlaps were mere coincidences. Then, in an American Indian studies class in my first term of grad school, I learned about U.S. settler colonialism, the process by which settlers take land from Indigenous people and attempt to replace them by validating settlers’ “superior” land claims through logics of race, religion, language, etc.

Settler colonialism relies on and advances the elimination of Indigenous people through genocide, disease, military removal, incarceration, forced assimilation, family separation, and more. Though popularized (at least in academic circles) by Patrick Wolfe, the idea originated by Wolfe’s own admission in Indigenous scholarship, literature, and communities, as J. Kēhaulani Kauanui has shown. For one example, check out Haunani Kay-Trask’s work on settler society in Hawai’i.

That I didn’t know about this phenomenon until graduate school was not a mistake. Settler knowledge systems — schools, archives, museums — also eliminate Indigenous presence. Think about it: Many of us don’t know whose lands we live on, let alone how those nations are doing today, even when we reside in places with (often mispronounced and misattributed) American Indian names.

Whittling Down Indigenous Land Holdings

Until recently, Japanese American incarceration and American Indian dispossession have often been treated as unrelated discussions. In reality, different oppressions reinforce and bolster one another.

We see this in different forms in Japanese American incarceration: the government taking reservation lands at Gila River and Poston without the CRIC and GRIC Councils’ consent; or exploiting Japanese American incarcerated labor to develop land for post-war homestead lotteries at Heart Mountain, Minidoka and Tule Lake. The history of Japanese American incarceration starkly reveals the processes through which settler colonialism dispossesses American Indians, destroys the land through resource extraction and promotes white settler property — using racialized incarcerated labor to do it.

Heart Mountain is a sacred site to the Apsáalooke, though as Grant Bulltail (Apsáalooke) put it, “your idea of something sacred and my idea of something sacred are a little bit different.” In 1851, a combination of U.S. treaties, military force, and Indian Affairs policies began to whittle down Apsáalooke landholdings, confining them first to a newly-defined 33 million acre reservation.

In 1868, another treaty lopped off the Wyoming side of the reservation as well as pieces of the Montana side. Though the treaty technically preserved hunting rights beyond the reservation, Apsáalooke access to Heart Mountain eroded as the OIA and U.S. military increasingly policed off-reservation movements. By 1904, the reservation was down to 2.2 million acres.

The ‘Whitening’ of the American Frontier

In 1896, Buffalo Bill Cody bought land, intending to build a town — Cody — where he could fund irrigation projects that, with the nearby construction of the railroad, would inflate property prices. By 1904, Cody’s projects had failed. With investors threatening lawsuits, the Reclamation Service bailed him out, dubbing its new purchase the “Shoshone Project.”

In 1908, Reclamation started releasing homesteads via lottery for 50 cents per acre. Any citizen or person intending to become a citizen was eligible, which excluded American Indians and Asian immigrants.

These policies were well-advertised on other Reclamation projects and among white settlers who had funds to cover the first few years of farming. As Paul Frymer writes, Reclamation “promoted the whitening of the American frontier.”

Moreover, it accomplished this by pushing out American Indians and harming the local environment. With dams hoarding the area’s water, dust storms buried irrigable land in silt, destroying crops several years running. Over-irrigation by newcomers unfamiliar with regional farming practices further damaged the land. Reclamation offered settlements up to $18,000 or bought farms back outright. From the offer of practically-free homesteads to white settlers and bail-outs when things went awry, we see the privileging of certain interests and the subjugation of others.

Despite its early struggles, by 1938 Reclamation had opened three of four homesteading divisions and was constructing a canal for the fourth. When World War II started, the Heart Mountain canal was still partially unlined and functionally useless. Water flushed through the unlined parts seeped into the soil, nearly causing the banks to collapse.

But in Japanese American incarceration, Reclamation saw an opportunity, proposing several sites where prisoners might develop irrigation infrastructure and turn land into homesteads for veterans after the war.

The other two Japanese American incarceration sites on Reclamation land were Tule Lake, site of the U.S.-Modoc War on Modoc homelands, and Minidoka, from which the Newe were removed in 1868. Minidoka is where the majority of the 55 Alaska Native incarcerees, removed for partial Japanese heritage or kinship ties with Japanese Americans, were assigned.

Commodifying Indigenous Resources

Land was not the only resource commodified at these sites. Since 1913, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) has expropriated Owens Valley water. As depicted in the documentary “Manzanar Diverted,” this has harmed the local environment and the health of the Nüümü (Owens Valley Paiute), settlers, and former incarcerees.

https://player.pbs.org/partnerplayer/TktHeq5XSkSUkwPkc9zCew==/?topbar=false&end=0&endscreen=true&start=0&autoplay=falsePOV: Manzanar, Diverted: When Water Becomes Dust (Trailer) | Native Americans, Japanese Americans and environmentalists defend their water from L.A.

Trailer | Manzanar, Diverted: When Water Becomes Dust

LADWP staff were also the first to suggest Poston as a WRA site in an (unsuccessful) effort to steer the federal government away from Manzanar. The LADWP didn’t have access to the Roosevelt administration and FBI pre-war reports demonstrating that the Japanese American “threat” to national security was unfounded. They simply preferred to shift the perceived risk to the CRIC instead of their own constituents.

The camp names also appropriated Indigenous histories: Granada, a concentration camp in Colorado, is more commonly known as Amache, initially a nickname for the camp post office taken from a 19th-century Cheyenne woman married to an early white settler in the area. Now the public is more likely to associate the name with the concentration camp than the woman to whom the name belongs.

According to Bernadette Pérez, Amache was herself imprisoned in her home in 1864 by U.S. troops to prevent her and her family from warning other Cheyenne and Arapahoes of the Sand Creek Massacre. The 2022 designation of the National Park Service’s Amache National Historic Site legitimated the nickname.

What would Amache have thought of having a concentration camp named after her?

History Repeating

Because many of the WRA staff came from the Department of Agriculture and the OIA, they were familiar with other agencies’ settler colonial policies and facilitated and exploited these policies in their WRA work. San Francisco Regional WRA Director E.R. Fryer came from a career in the OIA.

WRA Director Dillon Myer came from a career in the Department of Agriculture and, in 1950, began a three-year stint as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Myer’s OIA tenure is remembered for implementing policies pressuring American Indians to leave their lands and communities for menial city jobs — which looked remarkably similar to his Japanese American resettlement efforts.

Manzanar Divided: Mapping Convergence and Dislocation

These entanglements continued even after the war. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 tied Japanese American and Unangax̂ (Aleut) reparations together. By mid-June 1942, when Unangax̂ were removed for their own “safety,” the regional wartime threat was already subsiding and white settlers were permitted to remain. Relocated to abandoned canneries and mines, the Unangax̂ faced inadequate sanitation, drinking water and other provisions, as well as medical neglect so severe that one in 10 died.

Unfortunately, formal recognition has not raised public awareness of Unangax̂ World War II experiences during World War II, which are still little-known and infrequently-taught.

Growing Indigenous Land Access

Today, the land around Heart Mountain is a disorderly grid of ownership by the Bureau of Land Management, non-profits including the Nature Conservancy and the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center and privately-owned segments. Lush green fields and former barracks pristinely painted and reconfigured into single-family homes have replaced the sagebrush and dust Japanese Americans encountered in 1942. In 2011, a museum — designed to look like barracks — opened, writing the history of incarceration back into the landscape.

In 2019, the Supreme Court affirmed Apsáalooke off-reservation hunting rights in Wyoming.

The Return to Foretop’s Father, a gathering founded by the late Grant Bulltail to reassert Apsáalooke presence at Heart Mountain, just completed its twelfth gathering.

For two days, on a privately-owned campground at the base of the mountain, Apsáalooke put up tents and host a homemade meal featuring traditional Apsáalooke dishes with Apsáalooke dancers and musicians. The staff of the Nature Conservancy, which currently owns the Heart Mountain Ranch Preserve, welcome the Apsáalooke back to their own land.

The events are attended not only by Apsáalooke but also by local settlers and, increasingly, Japanese Americans attending the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center’s annual pilgrimage. These individuals and non-profits actively support this important program. Nationally, the Nature Conservancy fosters Indigenous land access, facilitating the return of 9,000 acres to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation earlier this year.

Still, the very impermanence of the Return to Foretop’s Father, the maneuvering of different landowners’ claims, the bureaucratic hurdles to schedule and participate in the hike are an indication of both settler support for this event and of the ways Apsáalooke access to the area continues to depend on the continued goodwill of local landholders.

And, as American Indians and other Indigenous people know too well, this support could easily disappear — whether from a change of heart, a shift in organizational policy or leadership or the sale of the land.

As the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation has joined the ranks of local landholders, Apsáalooke are still precariously positioned on their own homelands.

As Japanese American public history projects gain more visibility in U.S. history and on American landscapes, our organizations and communities can help advocate for Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship of the land and center these values in our commemorations of the incarceration — at Heart Mountain, certainly, but also beyond. After all, every Japanese American incarceration site was on Indigenous land — as is all land in what is today known as the U.S.