Source: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23780231231192389

Authors: Junia Howell, Ellen Whitehead, Elizabeth Korver-Glenn; Notes: Junia Howell, University of Illinois Chicago, Department of Sociology, 1007 W. Harrison Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7101, USA Email: jhowel4@uic.edu

Abstract

Initially, U.S. federally funded low-income rental housing was racially segregated and unequal. Activists decried this injustice and pressured legislators to introduce new practices and procedures. Since the passage of these initiatives in the 1960s, scholars have repeatedly documented ongoing racial inequality in housing at large. Yet rarely have researchers investigated whether racial inequality persists within governmentally subsidized housing units. By merging the restricted American Housing Survey with the American Community Survey at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center, the authors find that low-income renter subsidies are effective and beneficial but disproportionately grant White residents access to cheaper and higher quality units. Moreover, subsidized renters remain racially segregated across program type and neighborhoods. The authors discuss the implications of these findings for future research and policy decisions.

By the mid-1960s, Black, Chicanx, and American Indian activists’ strategic legal challenges and sustained direct-action campaigns ensured the U.S. public and their elected officials could no longer ignore the federal government’s role in creating and sustaining racially segregated and unequal housing conditions, especially within governmentally funded housing developments (Brown-Nagin 2022; Popkin et al. 2000; Taylor 2019).1 In response, a series of legislative acts, agency initiatives, and court orders decried the unjust practices and introduced new procedures aimed at reducing racial inequality. Unfortunately, most of these action steps were underfunded, void of enforcement mechanisms, superseded by new programs, and/or undercut by local officials unwilling to desegregate their communities (Ellen 2020; Taylor 2019; Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). Consequently, racially separate and unequal housing conditions have persisted (Faber 2020; Goetz 2018; Massey and Denton 1993).

Although researchers have repeatedly documented ongoing racial segregation and housing inequality at large, this work rarely investigates to what extent racial inequality persists within governmentally subsidized housing units and whether particular programs exacerbate this inequality. To begin to fill this gap in the literature, the present study uses nationally representative, geocoded data on low-income households to examine whether subsidized housing benefits are equally granted across racial groups. Specifically, we assess racial equity in low-income renters’ unit safety, affordability, and segregation, evidence that could assist policy makers’ and advocates’ efforts to ensure that government subsidies comply with fair housing legislation. Our novel analysis highlights the strengths of government-funded subsidies and the changes needed to ensure equity.

The Fight to Integrate Public Housing

Throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Black, Chicanx, and American Indian activists empirically demonstrated that federal subsidized housing programs were racially separate and unequal (Vale and Freemark 2012). These scholar activists pointed out how all federally subsidized housing programs were cloaked in anti-Black and anti-Indigenous bias, leading to the disproportionate demolition and displacement of Black and Indigenous communities and the repurposing of this land for housing White residents (Banner 2009; Baptist 2016; Dunbar-Ortiz 2014, 2021; Imbroscio 2021; Ruechel 1997). Using their compelling narratives and comprehensive data, they orchestrated lawsuits, public awareness initiatives, and direct-action campaigns challenging the constitutionality and morality of the government’s segregationist housing policies (Brown-Nagin 2022; Popkin et al. 2000; Taylor 2019). Under pressure, local and state governments began integrating all-White public housing developments.

Fearing desegregation, the 1961 Congress shifted federal resources from governmentally managed complexes to privately developed and managed units that would not need to comply with desegregation mandates (Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). As Congress privatized and defunded the programs, political pressure mounted on Washington to pass the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which prohibited racial, national origin, or religious discrimination in the selling, renting, or financing of housing units—including publicly subsidized units (Popkin et al. 2000). However, before the Act was passed, Northern White representatives feared the political consequences of racially integrating their own communities and negotiated a bill that seemingly appeased activists’ demands while eliminating enforcement mechanisms. Moreover, four months later, Congress passed the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, which further defunded public rental units in favor of homeownership subsidies (Gotham 2000; Taylor 2019).

White families unwilling to live in integrated public housing complexes were sold subsidized homes in new suburban areas. Simultaneously, families of color were offered predatory mortgages in historically redlined communities, further exacerbating racially separate and unequal housing conditions (Gotham 2000; Taylor 2019). Additionally, this act replaced public housing grants with loans, increasing the overall cost of subsidized housing and shifting resources from low-income renters to lenders (Johnson 2016). These policies continued the historical legacy of subsidizing more privileged residents’ housing at the expense of their marginalized neighbors.

As White families chose subsidized homeownership and privately managed housing complexes, publicly managed developments became majority residents of color. Simultaneously, elected officials used racist dog whistles to deliberately transform the public’s perception of publicly managed developments (Bloom 2008; Goetz 2018; Hannah-Jones 2012). Within only a few years, public housing complexes went from being perceived as desirable, decent, and affordable housing for “upstanding” White families to being perceived as crime ridden, filthy, and a last resort for families of color. The racist disdain for communities of color enabled the Nixon administration to cease funding for public housing construction, eliminate requirements for replacing condemned units, celebrate the demolition of public complexes (e.g., St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe), and incentivize the privatization of affordable housing (Ellen 2020; Goetz 2018; Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). These changes decreased the number of subsidized rental units and accelerated their privatization, especially through the expansion of Section 8 tenant vouchers.2

Building on the decades-long legacy of Black, Chicanx, and American Indian housing activism, scholars and activists of color empirically refuted the unfounded accusations regarding the failures of public housing and its negative consequences on residents’ well-being (e.g., Ladner 1971, 1973). Yet rather than elevating these theoretically and methodologically rigorous analyses, the predominant, historically White academic journals, presses, and institutions published and promoted scholarship that further reified notions of public housing complexes as crime ridden, poverty-stricken communities that needed to be disbanded (Fleming 2018; Goetz 2018; Ladner 1973; Pattillo 2013).

Granted, unlike the Nixon administration and other conservative voices that pushed for the complete elimination of publicly subsidized housing, White social scientists and elected officials on the political left argued that governmental housing support was needed for low-income residents (Goetz 2018). Moreover, they espoused the civil rights of individual Black, Latinx, and Indigenous residents to obtain decent and affordable housing. However, ironically, they perceived that Black, Latinx, and Indigenous residents could only receive decent and affordable housing if they “escaped” Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. That is, these scholars simultaneously affirmed individual equality while reifying the racist notion that majority Black, Latinx, and Indigenous spaces are inherently subpar and dangerous (Fleming 2018; Howell 2019; Itzigsohn and Brown 2020; Ladner 1973).3 Additionally, by focusing almost exclusively on Black public housing residents, this scholarship further solidified the false narrative that public housing is majority Black and undesirable (Howell 2019).

Most of this scholarship used the semiexperimental designs of the Gautreaux, Moving to Opportunity, and HOPE VI programs to compare the wellness of public housing residents who remained in place and those that were relocated to more affluent, White communities. Some of these studies concluded that relocated residents had improved mental and physical well-being (DeLuca et al. 2010; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2003; Ludwig et al. 2008, 2013). Yet their methodological designs did not enable them to disentangle the relocation and contextual effects. Thus, they relied on racist assumptions about communities of color and concentrated poverty to insinuate the observed outcomes were the result of living in Whiter, more affluent neighborhoods (Fleming 2018; Howell 2019; Rendón 2019).

These studies were used by politicians to justify the demolition of large public housing complexes, the privatization of public housing management, and the influx of tenant vouchers (Goetz 2018; Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995).4 In short, instead of holding the government accountable for desegregating and equalizing subsidized housing programs by continuing to empirically evaluate whether government subsidies equally provided safe, affordable, and desegregated units to all racial groups, scholars’ work reified the government’s anti-Black narratives that stigmatized Black neighborhoods and conflated poverty with Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. We address this gap in the literature by examining whether subsidized housing units remain racially separate and unequal.

Mechanisms Perpetuating Racial Inequality in Subsidized Housing Programs

Although the extent of racial inequity and segregation in contemporary governmental housing programs remains unknown, the literature posits two primary explanations for ongoing inequality: personal preferences and policy provisions.

Personal Preferences

Using innovative survey designs, factorial experiments, ethnographic observations, and in-depth interviews, scholars have repeatedly shown White residents continue to prefer White neighborhoods (Howell and Emerson 2018; Krysan and Crowder 2017; Lareau and Goyette 2014). Likewise, research has illuminated how landlords’ racist stereotypes and practices segregate renters and provide higher quality housing at lower price points for White tenants (Faber and Mercier 2022; Korver-Glenn and Locklear forthcoming; Korver-Glenn et al. 2023; Massey and Lundy 2001; Rosen, Garboden, and Cossyleon 2021). In short, within the private rental market, individual preferences of residents and landlords sort tenants into racially separate and unequal units.

Some academics and public officials assume individual preferences observed in the private rental market also influence housing subsidy programs, especially programs like tenant vouchers that use private market units (Faber and Mercier 2022; Rosen and Garboden 2022; Rosen et al. 2021). Given that these individual preferences are driven by larger cultural conditions, we can infer that their contribution to racial inequality in rental units would be comparable across market rate and government subsidized units. Thus, any differences between the racial inequality in market rate and government subsidized housing is likely due to the second primary explanation for ongoing injustice: policy provisions.

Policy Provisions

As outlined earlier, from their inception, U.S. federal housing subsidies have systematically displaced and constrained people of color to subpar housing (Baptist 2016; Du Bois 1899; Dunbar-Ortiz 2021; Robinson 1983). Even as activists were successfully arguing for desegregating programs, Congress increasingly privatized and diversified the federal housing subsidies so that they would not have to comply with the new racial equity mandates (Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). This diversity across program types and management has resulted in housing subsidies varying widely in their quality, cost, and racial integration (Schwartz 2021).

Although scholars have uncovered how the origins of this program variation had racist intentions, it remains unclear whether differences in program criteria or management continue to perpetuate racial inequality and segregation in the contemporary government housing programs. Yet prior work provides clues about how such variation shapes ongoing subsidized housing inequities. For example, historically and contemporarily, Black residents who qualify for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) subsidies are disproportionately filtered into the tenant voucher program, which is the most expensive of the housing subsidy programs for both the government and the residents (Schwartz 2021). Unlike residents in publicly funded developments, recipients of tenant vouchers are required to pay the difference between what the landlord is charging for rent and the maximum subsidy contribution, often exceeding 40 percent of their income (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2019). As a result, Black subsidized renters are likely paying more for their units than their White counterparts. Likewise, Indigenous renters are more likely to receive government housing subsidies through federal programs designated exclusively for Tribal citizens with their own sets of quality standards and price parameters (e.g., Cortelyou 2001). Thus, Indigenous subsidized renters are likely to have distinct experiences from their non-Indigenous counterparts. Finally, tracing back to the Housing Act of 1956, subsidized housing for older adults is often age restricted, disproportionately White, and well maintained (Vale and Freemark 2012).5 The higher concentration of White renters in these developments contributes to White subsidized renters having higher quality units than their counterparts of color.

Together, the existing literature suggests that persistent racial inequity within housing subsidy programs is likely due to renters’ and landlords’ personal preferences and the programs’ policy provisions. Yet it remains unclear to what extent this inequity is present and how much of it can be explained by these primary mechanisms. Thus, to fill this gap in the literature, we merged restricted federal agency data to investigate whether subsidized housing remains separate and unequal.

Data and Methods

Datasets

To empirically examine whether racial inequality and segregation persist in government subsidized housing, we combined two U.S. Census Bureau surveys: the American Housing Survey (AHS) and the American Community Survey (ACS). Sponsored by HUD and conducted by the Census Bureau, the AHS is the longest running nationally representative survey on housing units. We applied for and were granted access to the geocoded, restricted version of the 2017 data, enabling us to link AHS units to ACS data on neighborhood demographics. The ACS collects annual data on residents’ characteristics and calculates aggregated demographic estimates for various geographic units. To match our AHS time frame, we used the ACS 2013–2017 five-year summary files and defined neighborhoods as census tracts. We examined all AHS renters eligible for HUD-sponsored assisted housing programs, whether or not they received a housing subsidy. We determined eligibility using HUD’s income limits for each county and household size.6

Housing Equity and Segregation

To examine whether governmentally subsidized housing remains racially separate and unequal, we evaluated rental unit safety, affordability, and segregation. We operationalized safety as the absence of unsafe conditions, affordability as housing cost and rent unaffordability, and segregation as neighborhood isolation.

Unsafe Conditions

Following precedent, we assessed unit quality by empirically examining the number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions within each unit. We conceptualize the following conditions as unsafe or unhealthy: exposed wires, blown fuses, broken electrical outlets, broken furnace, broken toilets, water supply interruption, sewage failure, rodent infestation, cockroach infestation, foundation damage, roof damage, broken windows, unstable exterior walls, unstable floors, and mold.7 We calculated the total number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions for each unit. Mirroring HUD’s classifications of inadequate housing units, we capped the number of unsafe conditions at four, adjusting for the variable’s rightward skew. We used the variable as continuous to reflect the additive effect of unsafe conditions on renter experiences.

Housing Cost

We conceptualized housing cost as rent and utility payments. We used the AHS’s total housing cost variable (tothcamt), which includes rent payments, utility bills, insurance, and other monthly housing expenses that the renter pays out of pocket. This does not include the amount the government pays to subsidize the cost. For our models, we used the square-root transformation of this variable.

Rent Unaffordability

Mirroring common measures of housing affordability, we divided the total housing cost, mentioned earlier, by the sum of all income for all household members 16 years old or older (hincp). This continuous variable reflects the proportion of household income spent on housing.

Neighborhood Isolation

We calculated neighborhood isolation as the proportion of the census tract that racially identifies as the same racial category as the respondent divided by the overall proportion of that racial category in the county. Conceptually, values between 0 and 1 can be interpreted as residents who live in a neighborhood where their racial group is underrepresented while values greater than 1 signify residents are living in a neighborhood where their racial group is concentrated. To adjust for the rightward skew of this variable, we used a logarithmic transformation.

Racial Classification

We defined a household’s racial classification as the self-reported race of the tenant who completed the AHS. Following the empirical findings of Howell and Emerson (2017), we grouped respondents’ answers into five categories: Latinx, White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), and Asian. The Latinx category included all individuals who identified as Hispanic, no matter their racial identity. White was categorized as respondents who identify as non-Hispanic and only White. Black individuals included all people who identify as non-Hispanic and Black. This included individuals who identify as only Black as well as those who identified as Black and White, Black and AI/AN, Black and Asian, Black and Pacific Islander, or any combination of three or four races that includes Black. AI/AN renters included those who identified as non-Hispanic and AI/AN as well as those who identified as non-Hispanic AI/AN and White, Asian, and/or Pacific Islander. Finally, the Asian classification includes both Asian and Pacific Islander renters who were non-Hispanic. This category also included individuals who identify as both Asian and Pacific Islander as well as those who identified as White and Asian and/or Pacific Islander.

Subsidy Program

To identify how the type of housing subsidy might be affecting the observed racial inequality, we divided government subsidies into four categories: HUD-funded, publicly managed developments; HUD-funded, privately owned and managed developments; HUD-funded tenant vouchers; and other governmental subsidies.

HUD-Funded Public Developments

We operationalize these as all complexes owned and operated by public housing authorities that receive HUD funding.8 After the collection of AHS data, HUD uses respondents’ addresses to identify which units are located within housing complexes that are currently receiving HUD funding. They further delineated these units by the type of subsidized unit and make this available in an imputed, restricted variable (hudsub_iuf). We used their classification to identify HUD-funded, public developments.

HUD-Funded Private Developments

We define private developments as privatively owned and managed developments that receive HUD funding. Some of these complexes were publicly built and managed complexes that were sold in recent decades to private organizations to manage while other developments were built by private organizations but funded through federal subsidies. No matter their original construction, today these complexes are heavily subsidized through federal funds, but the private management companies determine resident qualifications, rental cost, and unit quality (Schwartz 2021; Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). We also identified these complexes using the HUD imputed variable provided in the restricted AHS.

HUD-Funded Tenant Vouchers

We also use HUD’s imputed variable to identify all addresses currently registered as using the housing choice voucher program. These units are selected by the voucher holder and privately owned and managed.

Other Governmental Subsidies

Lastly, we categorize all government-funded housing subsidies that are not currently funded by HUD as other governmental subsidies. This includes housing complexes owned and operated by local public housing authorities that do not receive funding from HUD, privately owned and managed subsidized housing developments funded by local and state subsidies, and other federal government subsidies (e.g., Small Business Administration grants and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Refugee Resettlement Program). We identified these units as those where the respondent themselves reported living in public housing, using a tenant voucher, or receiving another government subsidy (rentsub) yet the address was not identified by HUD as currently receiving assistance through a HUD program.

Renter Qualifications

As mentioned earlier, how housing subsidy types are implemented varies on the basis of the populations being served (e.g., older single adults vs. families). To examine how differences in renter demographics might contribute to observed racial inequality, we controlled for four key qualifications used to determine residents’ eligibility: older adult, citizen, single adult, and children in the household.

Older Adult

Since 1956, select subsidy housing projects have been designated for older adults (Schwartz 2021). To capture the influence of age requirements, we use the Section 202 Supportive Housing for the Elderly Program guidelines and define older adults as all persons 62 years or older.

Citizen

To qualify for any HUD-funded housing subsidies, residents must be U.S. citizens or eligible immigrants. The AHS does not collect detailed immigration status information. Thus, we were not able to determine whether residents would qualify for subsidized housing under this provision. That said, we were able to determine citizenship status, which differentiates between the majority of the eligible and ineligible residents. We operationalized citizens as all residents who are U.S. born, born abroad to U.S. parents, or naturalized citizens.

Single Adult

Historically and contemporarily, marital status is one factor considered for some housing subsidies. We defined single adults as the adult respondent not being legally married nor living with a romantic partner.

Children in the Household

Finally, the presence of children in the household is a key factor considered for many housing subsidy programs. We operationalized households with children as all families with at least one dependent younger than 18 years living in the housing unit.

Property Characteristics

Given that the housing subsidy programs were developed in different decades under distinct urban planning ideologies, some are older multiunit apartment complexes, others are newer townhouses, and still others are single family dwellings. To identify the role property features might play in observed racial inequity, we controlled for three key property characteristics: decade built, multiunit structure, and total rooms.

Decade Built

Older buildings often have more unsafe conditions but are also more affordable. To control for this factor, we identify the property’s construction decade, defined as the first year in the decade. To ensure participant anonymity, AHS recoded all structures built before 1910 as built during the 1910s.9

Multiunit Structure

The differences between single- and multifamily structures can be substantial for maintenance and rental costs. Thus, we created a binary variable that distinguishes whether the unit is located in a single- or multifamily building.10

Total Rooms

Last, we controlled for the total number of rooms within the unit. Rooms included bedrooms, kitchens, dining rooms, and other finished rooms yet excluded unfinished basements, attics, porches, or garages. Given the variable’s rightward skew, we used a square-root transformation for all models.

Contextual Factors

Regional and neighborhood racial segregation means that racial groups are not equitably spread across the country (e.g., Asian residents are disproportionately concentrated in coastal counties and Black residents are concentrated in the South). Consequently, some of the observed racial inequality might be due to regional differences in housing subsidy programs. To isolate how contextual factors are contributing to observed racial inequality, we controlled for three key contextual factors: neighborhood poverty rate, neighborhood vacancy rate, and the county’s mean income.

Neighborhood Poverty

Building on previous studies that demonstrate a correlation between property maintenance and neighborhood poverty (Leonard 2016), we defined neighborhood poverty as the proportion of residents within the census tract living at or under the federal poverty line.

Neighborhood Vacancy Rate

We measured neighborhood vacancy rate as the proportion of total housing units in the neighborhood that are currently unoccupied. To adjust for the rightward skew of this variable, we used a logarithmic transformation for all models.

County’s Mean Income

Finally, we measured regional affluence with the county’s mean income.11 Like neighborhood vacancy rate, we used a logarithmic transformation to ensure the rightward skew did not unduly influence our models.

Statistical Models

To account for the geographic stratification of the AHS’s sampling frame, we used random effects regressions to estimate results. Our unit of analysis was housing units embedded within counties. We used the Stata command xtreg to estimate these models.12 In all our models, continuous variables are standardized to ease comparison.

Results

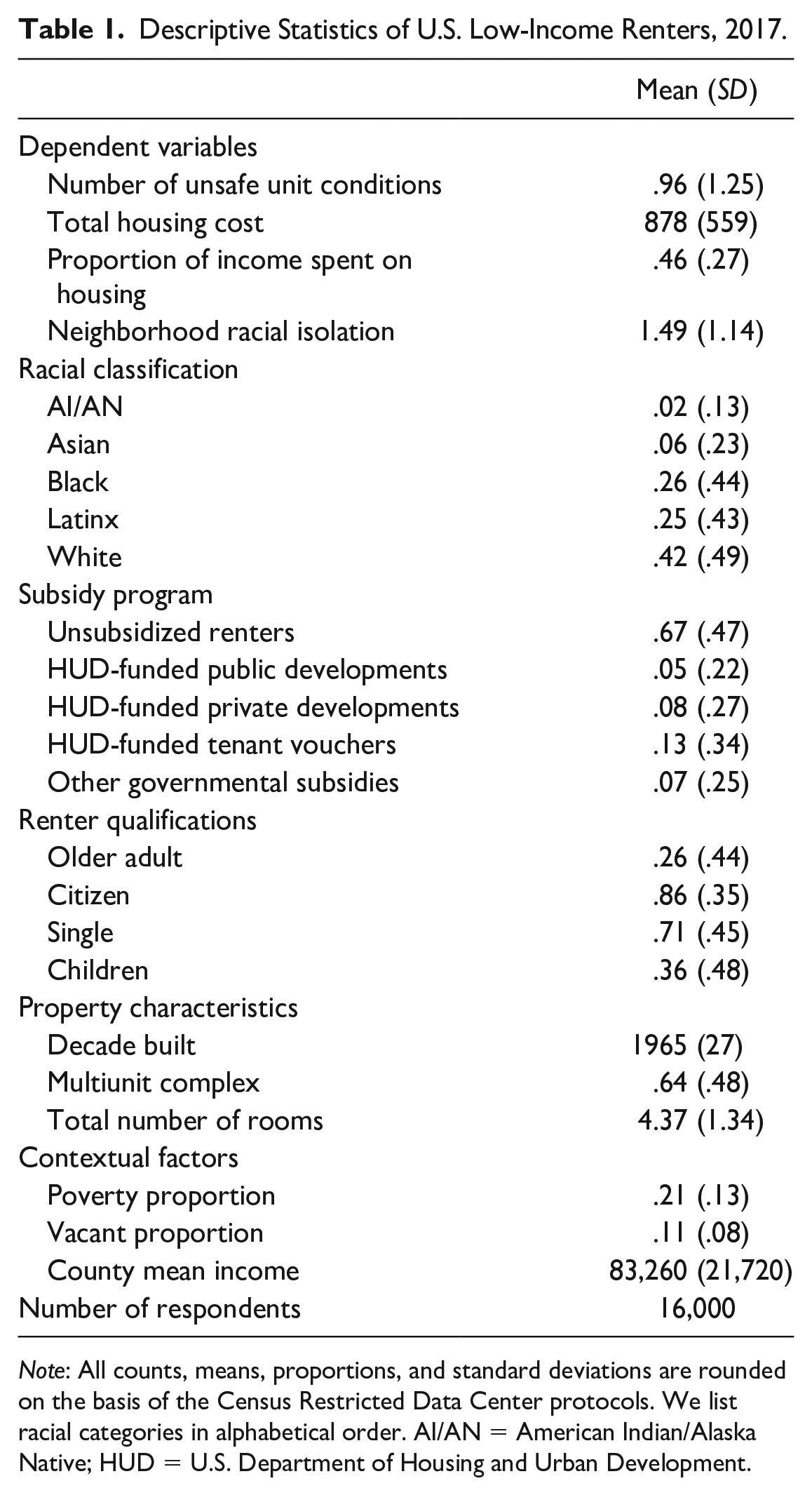

Despite the fact that people of color constitute only 38 percent of U.S. residents, they account for 58 percent of renters eligible for HUD’s housing subsidies because of the detrimental effects of historical and contemporary White supremacy. That said, 42 percent of low-income renters are White, which is still the modal racial category (see Table 1). In other words, unlike portrayals in popularized media reports and ethnographies, White renters still make up a substantial number of those eligible for and those receiving housing subsidies. Thus, the question that was critical in the 1950s and 1960s is still relevant today: are AI/AN, Asian, Black, Latinx, and White renters provided equitable governmentally subsidized units for comparable prices?Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of U.S. Low-Income Renters, 2017.

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |

| Number of unsafe unit conditions | .96 (1.25) |

| Total housing cost | 878 (559) |

| Proportion of income spent on housing | .46 (.27) |

| Neighborhood racial isolation | 1.49 (1.14) |

| Racial classification | |

| AI/AN | .02 (.13) |

| Asian | .06 (.23) |

| Black | .26 (.44) |

| Latinx | .25 (.43) |

| White | .42 (.49) |

| Subsidy program | |

| Unsubsidized renters | .67 (.47) |

| HUD-funded public developments | .05 (.22) |

| HUD-funded private developments | .08 (.27) |

| HUD-funded tenant vouchers | .13 (.34) |

| Other governmental subsidies | .07 (.25) |

| Renter qualifications | |

| Older adult | .26 (.44) |

| Citizen | .86 (.35) |

| Single | .71 (.45) |

| Children | .36 (.48) |

| Property characteristics | |

| Decade built | 1965 (27) |

| Multiunit complex | .64 (.48) |

| Total number of rooms | 4.37 (1.34) |

| Contextual factors | |

| Poverty proportion | .21 (.13) |

| Vacant proportion | .11 (.08) |

| County mean income | 83,260 (21,720) |

| Number of respondents | 16,000 |

Note: All counts, means, proportions, and standard deviations are rounded on the basis of the Census Restricted Data Center protocols. We list racial categories in alphabetical order. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; HUD = U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

As seen in Table 2, White renters live in units with fewer unsafe and unsanitary conditions compared with their AI/AN, Black, and Latinx counterparts. However, they are charged less for these higher quality units than their Asian, Black, and Latinx counterparts. Additionally, White renters are the least likely to be racially isolated. In short, government subsidized housing is still racially segregated and unequal with White renters receiving the highest quality units for the least cost.Table 2. Coefficients from Regressions Predicting Racial Inequality in Unit Quality, Cost, Affordability, and Racial Isolation across Low-Income Renters, 2017.

| Unsafe Unit Conditions | Total Housing Cost | Proportion of Income Spent on Housing | Neighborhood Racial Isolation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsubsidized Renters | Subsidized Renters | Unsubsidized Renters | Subsidized Renters | Unsubsidized Renters | Subsidized Renters | Unsubsidized Renters | Subsidized Renters | |

| Racial classification (reference: White) | ||||||||

| AI/AN | .44 (.08)* | .48 (.09)* | −.05 (.07) | −.19 (.08)* | −.01 (.08) | −.09 (.09) | −.30 (.08)* | .08 (.09) |

| Asian | −.15 (.04)* | .00 (.06) | .36 (.04)* | .18 (.06)* | .05 (.04) | .14 (.07)* | .51 (.04)* | .42 (.07)* |

| Black | .16 (.03)* | .26 (.03)* | .03 (.02) | .17 (.03)* | .03 (.03) | .16 (.03)* | .66 (.02)* | 1.10 (.03)* |

| Latinx | .13 (.02)* | .24 (.04)* | .17 (.02)* | .26 (.04)* | .00 (.02) | .12 (.04)* | .50 (.02)* | .67 (.04)* |

| Constant | −.04 (.02)* | −.20 (.02)* | .13 (.02)* | −.76 (.02)* | .01 (.03) | −.24 (.04)* | −.33 (.01)* | −.50 (.02)* |

| R2 | .0115 | .0189 | .0271 | .0178 | .0003 | .0065 | .0940 | .1929 |

| Number of respondents (counties) | 10,500 (200) | 5,300 (150) | 10,500 (200) | 5,300 (150) | 10,500 (200) | 5,300 (150) | 10,500 (200) | 5,300 (150) |

Note: All counts, coefficients, standard errors, and R2 values are rounded on the basis of the Census Restricted Data Center protocols for model disclosures. These rounding protocols result in the summation of the unsubsidized and subsidized renter count not equaling the total renter count. However, in the nonrounded tables this is not the case. We list racial categories in alphabetical order. The dependent variables are the number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions, the total monthly rent and utility payments, the proportion of total household income spent on rent and utility payments, and the racial proportion of the census tract matching the respondents’ race divided by the overall proportion of that racial category in the county. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native.

*

Denotes that the coefficient is statistically significantly different from zero at p < .05.

Figure 1 visualizes these differences in real-world terms. On average, AI/AN, Black, and Latinx subsidized renters all have over one unsafe condition in their housing units, while White and Asian renters have less than one. Although receiving lower quality units, Latinx subsidized renters pay $110 more a month than White subsidized renters, a 25 percent upcharge. Black and Asian subsidized renters pay less than Latinx subsidized renters, but they still pay $75 more a month than their White counterparts, a 17 percent upcharge. Put another way, Asian, Black, and Latinx subsidized households spend, on average, 5 percent more of their household income on housing than their White subsidized counterparts. Conversely, AI/AN subsidized renters pay the least, paying $72 less a month than their White counterparts. Yet AI/AN and White renters spend a comparable proportion of their household incomes on housing.

Not only are White subsidized renters receiving higher quality units while paying less, but subsidized renters remain segregated in distinct neighborhoods. The average White subsidized renter lives in a census tract that is nearly 70 percent White, while Asian, Black, and Latinx subsidized renters live in neighborhoods that are only 30 percent White. To be clear, we do not ascribe to the notion that White neighborhoods are more desirable or advantageous for subsidized renters. Thus, it is not inherently problematic that subsidized renters of color are living in communities of color. Rather, the neighborhood proportions illuminate that White subsidized renters are not residing next to their subsidized counterparts of color. The racial segregation of subsidized renters persists with renters being housed in communities where their own racial group is disproportionately concentrated.

As some scholars have hypothesized, the contemporary racial inequality in subsidized housing programs could be the result of personal preferences. If this were the case, racial inequality across low-income renters would be comparable for subsidized and unsubsidized tenants. Table 2 therefore compares the racial inequality across low-income subsidized and unsubsidized renters and demonstrates that while the general racial inequality patterns are similar, racial inequality is notably larger for subsidized renters.

To be clear, all subsidized renters have fewer unsafe conditions and lower monthly costs than their racial group counterparts without subsidies. Yet the racial inequality among subsidized renters is larger than the racial inequality among unsubsidized renters. In fact, White and Asian renters in both subsidized and unsubsidized housing units have fewer unsafe conditions than all AI/AN, Black, and Latinx renters, subsidized or not. Conversely, all unsubsidized renters are paying double what subsidized renters pay. The average low-income renter in the private market spends 46 percent of their income on housing. However, all racial groups in the private market are paying equitable prices. In short, although government subsidies make housing more affordable and higher quality for participating renters, the racial inequality between subsidized renters is considerably higher than observed in the private market.

Likewise, racial inequality in neighborhood isolation is higher among subsidized renters than their unsubsidized counterparts. Black subsidized renters are the most likely of all renters (subsidized or unsubsidized) to be located in neighborhoods where their own race is disproportionately concentrated. Much like the observations that served as the impetus for the 1976 Supreme Court desegregation mandate, governmentally subsidized housing is exacerbating Black residents’ neighborhood isolation, even more than the racist processes within the broader housing market. Although the degree to which this is happening is less severe for AI/AN, Asian, and Latinx renters, the story is the same. AI/AN, Asian, and Latinx subsidized renters are more segregated into AI/AN, Asian, and Latinx neighborhoods (respectively) than their AI/AN, Asian, and Latinx unsubsidized counterparts (see Table 2).

In short, the racial inequality among subsidized renters is greater across all outcomes than the racial inequality observed in the private rental market. This suggests that it is not merely personal preferences driving the observed inequality but also the government programs’ policy provisions that likely contribute to the observed inequities. To further investigate these mechanisms, we first examine the racial segregation across the various types of subsidy programs.

To avoid desegregation, many White public housing complexes were sold to private companies that received federal funding but set their own tenant eligibility requirements. This historical legacy reverberates today, with White subsidized renters being disproportionately concentrated in HUD-funded, privately managed developments and other government subsidies while being least likely to live in HUD-funded, publicly managed housing (see Table 3). Conversely, Black subsidized renters are disproportionately concentrated in publicly managed complexes and the tenant voucher program, which was designed for Black residents so that HUD was not legally responsible for their segregation. AI/AN subsidized renters, on the other hand, are less likely to have vouchers and much more likely to have other government subsidies, reflecting how other government agencies provide housing subsidies to many Tribal citizens. The Latinx and Asian communities also have particular histories and migration journeys that have shaped their distribution across subsidy types, with Asian renters most likely to live in HUD-funded, privately managed complexes and Latinx tenants most likely to receive other government subsidies.Table 3. Racial Distribution across Subsidy Programs, 2017.

| All Subsidized Renters | Public Developments | Private Developments | Tenant Vouchers | Other Governmental Subsidies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial classification | |||||

| AI/AN | .02 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .05 |

| Asian | .05 | .04 | .06 | .04 | .06 |

| Black | .38 | .48 | .32 | .45 | .23 |

| Latinx | .18 | .19 | .15 | .19 | .21 |

| White | .37 | .28 | .44 | .31 | .46 |

| Number of respondents | 5,300 | 800 | 1,300 | 2,100 | 1,000 |

Note: All counts and proportions are rounded on the basis of the Census Restricted Data Center protocols. These rounding protocols result in the summation of the public developments, private developments, tenant vouchers, and other governmental subsidies counts not equaling the total subsidized renter count. However, in the nonrounded tables this is not the case. We list racial categories in alphabetical order. The dependent variables are the number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions, the total monthly rent and utility payments, the proportion of total household income spent on rent and utility payments, and the racial proportion of the census tract matching the respondents’ race divided by the overall proportion of that racial category in the county. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native.

Additionally, racial groups are filtered into certain housing subsidy programs or developments on the basis of their renter qualifications. As discussed earlier, when White families were leaving publicly managed complexes for the more economically advantageous governmentally funded homeownership subsidies, the qualifications for housing assistance were expanded to include White older adults (Schwartz 2021). Today, White subsidized renters continue to be disproportionately older adults, and AI/AN, Asian, Black, and Latinx renters are disproportionately families with children. Rather than integrating older adults and families, most subsidized housing programs separate older adults. Age and family composition segregation, combined with the racial demographic difference, exacerbates the racial segregation in subsidized housing. To empirically investigate how this segregation across program type and program management contributes to the observed inequality, we control for these policy provisions.

Table 4 suggests that racial inequality across subsidized unit quality, cost, and segregation is partially explained by the operationalized policy provisions. Specifically, segregation across subsidy program, renter qualifications, property characteristics, and contextual factors explains 23 percent of the unit condition inequality between White and AI/AN renters, 73 percent of unit condition inequality between White and Black renters, and 58 percent of the unit condition inequality between White and Latinx renters. This is due largely to families with children residing in more unsafe conditions than older adults, as observed in ethnographic research (Desmond 2016; Rosen and Garboden 2022; Rosen et al. 2021). Racial segregation across property age, size, and location explains a significant proportion, but not all, of the observed racial inequality in unit quality.Table 4. Coefficients from Regressions Predicting Racial Inequality in Unit Quality, Cost, Affordability, and Racial Isolation, 2017.

| Unsafe Unit Conditions | Total Housing Cost | Proportion of Income Spent on Housing | Neighborhood Racial Isolation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial classification (reference: White) | ||||

| AI/AN | .37 (.09)* | −.21 (.07)* | −.10 (.09) | .02 (.09) |

| Asian | .01 (.07) | .03 (.05) | .19 (.07)* | .25 (.07)* |

| Black | .07 (.03)* | .15 (.03)* | .10 (.03)* | .93 (.03)* |

| Latinx | .10 (.04)* | .17 (.03)* | .08 (.04) | .55 (.04)* |

| Subsidy program (reference: public) | ||||

| Private developments | −.06 (.04) | .08 (.04)* | .01 (.04) | .10 (.05)* |

| Tenant vouchers | .03 (.04) | .35 (.03)* | .34 (.04)* | .03 (.04) |

| Other governmental subsidies | .05 (.05) | .68 (.04)* | .41 (.05)* | .04 (.05) |

| Renter qualifications | ||||

| Older adult | −.17 (.03)* | −.06 (.03)* | .03 (.03) | .11 (.03)* |

| Citizen | .07 (.06) | −.08 (.04) | −.11 (.06)* | .05 (.06) |

| Single | −.04 (.04) | −.33 (.03)* | .20 (.04)* | −.02 (.04) |

| Children | .18 (.04)* | .05 (.03) | .01 (.04) | .09 (.04)* |

| Property characteristics | ||||

| Decade built | −.13 (.01)* | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | −.03 (.01)* |

| Multiunit complex | −.12 (.03)* | −.20 (.03)* | −.23 (.03)* | −.11 (.04)* |

| Total number of rooms, transformed | .00 (.02) | .19 (.01)* | .09 (.02)* | .05 (.02)* |

| Contextual factors | ||||

| Poverty proportion | .09 (.01)* | −.08 (.01)* | −.01 (.01) | .19 (.01)* |

| Vacant proportion, transformed | .04 (.01)* | −.03 (.01)* | .00 (.01) | .07 (.01)* |

| County mean income, transformed | .03 (.01)* | .13 (.01)* | .02 (.02) | .16 (.01)* |

| Constant | −.07 (.08) | −.41 (.06)* | −.31 (.08)* | −.50 (.08)* |

| R2 | .0851 | .2826 | .0740 | .2405 |

| Number of respondents (counties) | 5,300 (150) | 5,300 (150) | 5,300 (150) | 5,300 (150) |

Note: All counts, coefficients, standard errors, and R2 values are rounded on the basis of the Census Restricted Data Center protocols for model disclosures. The dependent variables are the number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions, the total monthly rent and utility payments, the proportion of total household income spent on rent and utility payments, and the racial proportion of the census tract matching the respondents’ race divided by the overall proportion of that racial category in the county. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native.

*

Denotes that the coefficient is statistically significantly different from zero at p < .05.

Policy provisions also explain some, although much less, of the racial inequality in housing cost and affordability. The difference between White and AI/AN renters’ housing costs and affordability does not materially change with the introduction of control variables. Conversely, the control variables explain all the inequality across White and Asian renters’ housing costs. That said, these controls are unable to explain the difference in the proportion of income White and Asian families spend on housing. In fact, the findings demonstrate the opposite: the controls reveal the inequality in affordability is even larger than it first appears. Together, these findings suggest that while Asian subsidized renters are paying comparable amounts as their White subsidized neighbors in the coastal counties where they are concentrated, their incomes are lower, resulting in a larger housing burden on Asian renters.

The inequality between White and Black renters’ cost and affordability is slightly reduced when the policy provisions are taken into consideration: a 10 percent reduction in cost and a 38 percent reduction in affordability. This is due largely to Black renters’ concentration in the more expensive tenant voucher program and single-family homes. Although these conditions explain some of the inequality, the majority of cost and affordability inequality between White and Black subsidized renters remains unexplained by these factors. In other words, Black households renting comparable units from the same government program in the same counties are paying $70 more a month (a 14 percent upcharge) and 10 percent more of their household income on rent than their White counterparts. Finally, a third of the inequality between White and Latinx subsidized renter costs and affordability is explained by their segregation across programs and counties. Yet like Black renters, Latinx renters still pay about 14 percent more per month than their White counterparts for the same type of units within the same context and program type.

Turning to neighborhood isolation, we see the racial distribution across subsidy program, renter qualifications, property characteristics, and contextual factors explains 40 percent of the racial inequality in neighborhood isolation between White and Asian renters but only 18 percent and 15 percent of the racial inequality in neighborhood isolation for Latinx and Black renters, respectively. The reduction in inequality is the result of higher neighborhood isolation among older adult complexes, privately managed developments, and subsidized units in wealthy counties. That said, the majority of the racial inequality in neighborhood isolation, especially for Black and Latinx renters, remains even when these other factors are taken into consideration.

Discussion

By merging the restricted AHS with the ACS at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center, the present study systematically investigated whether government subsidized housing is racially integrated and equal. Across unit quality, total cost, affordability, and neighborhood isolation, we found governmental subsidized housing is still separate and unequal. Specifically, Black and Latinx subsidized renters live in units with more unsafe conditions than White subsidized renters, yet they are simultaneously paying more, both in raw dollar amounts and relative to their income, than their White counterparts. Moreover, Black and Latinx renters in governmentally subsidized housing are disproportionately housed in neighborhoods where their racial group is concentrated. Each of these inequities is starker for Black residents than their Latinx counterparts, but both groups experience lower quality units for a higher price tag in more segregated areas than their White neighbors.

The inequality faced by Asian and AI/AN renters is slightly more complicated. Asian renters living in governmentally funded housing have comparable unit quality as their White counterparts. Yet they pay considerably more for these units. Granted, part of the price inequity is due to Asian subsidized renters being concentrated in more expensive cities. However, these renters also make less than their White counterparts in these regions, resulting in Asian subsidized renters paying notably higher proportions of their income on housing than their White counterparts. Moreover, like their Black and Latinx peers, Asian renters living in governmentally funded housing are disproportionately concentrated into Asian neighborhoods.

AI/AN subsidized renters live in lower quality units with more unsafe and unhealthy conditions than any other racial group. Their monthly payment for these units, in both dollar amounts and the proportion of their income, is less than all the other racial groups. Although it might benefit these renters to have lower monthly costs, the low quality of these units means AI/AN subsidized renters are still suffering the negative consequences of inequality within governmentally subsidized housing.

In short, U.S. contemporary housing programs continue to uphold the centuries-old pattern of providing the highest quality units at the lowest prices to White settlers while segregating AI/AN, Asian, Black, and Latinx people into lower quality units at higher prices. Moreover, the racial inequality between governmentally subsidized renters is greater on every outcome than the racial inequality observed in the low-income unsubsidized rental market. This suggests it is not merely the personal preferences of landlords and renters but the specific policies and procedures within the government subsidized housing programs themselves. That said, it is extremely important to point out that defunding governmental housing programs or increasing the number of tenant vouchers will not address the observed racial inequities.

Faced with the injustices of the racially segregated public housing complexes, political leaders in the 1960s and 1970s responded by decrying, defunding, and privatizing governmental housing programs. As we can now see, this did not address the racial inequality in subsidized housing programs. In fact, HUD-funded project-based subsidies—those most criticized within public discourse—provide the highest quality, most affordable units for low-income tenants at the cheapest price point for the government (see Table 5; see also Schwartz 2021).Table 5. Coefficients from Regression Models Predicting Unit Quality, Cost, Affordability, and Racial Isolation, 2017.

| Unsafe Unit Conditions | Total Housing Cost | Proportion of Income Spent on Housing | Neighborhood Racial Isolation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Subsidy program (reference: unsubsidized) | ||||||||

| Public developments | .07 (.04)* | −.08 (.04)* | −1.17 (.03)* | −.98 (.03)* | −.40 (.04)* | −.42 (.04)* | .25 (.04)* | .06 (.04) |

| Private developments | −.22 (.03)* | −.13 (.03)* | −1.27 (.03)* | −1.01 (.02)* | −.49 (.03)* | −.50 (.03)* | .05 (.03) | .06 (.03)* |

| Tenant vouchers | −.02 (.02) | −.03 (.02) | −.78 (.02)* | −.66 (.02)* | −.04 (.02) | −.08 (.02)* | .15 (.02)* | .11 (.02)* |

| Other governmental subsidies | −.08 (.03)* | .00 (.03) | −.53 (.03)* | −.41 (.03)* | −.06 (.03) | −.07 (.03)* | −.08 (.03)* | −.07 (.03)* |

| Renter qualifications | ||||||||

| Older adult | −.13 (.02)* | −.15 (.02)* | .07 (.02)* | .02 (.02) | ||||

| Citizen | .07 (.02)* | −.09 (.02)* | −.14 (.02)* | −.25 (.02)* | ||||

| Single | −.03 (.02) | −.17 (.02)* | .24 (.02)* | .05 (.02)* | ||||

| Children | .20 (.02)* | .12 (.02)* | −.01 (.02) | .13 (.02)* | ||||

| Property characteristics | ||||||||

| Decade built | −.12 (.01)* | .04 (.01)* | .04 (.01)* | −.05 (.01)* | ||||

| Multiunit complex | −.18 (.02)* | .03 (.02)* | −.05 (.02)* | −.05 (.02)* | ||||

| Total number of rooms, transformed | −.02 (.01)* | .17 (.01)* | .08 (.01)* | .05 (.01)* | ||||

| Contextual factors | ||||||||

| Poverty proportion | .11 (.01)* | −.05 (.01)* | .03 (.01)* | .23 (.01)* | ||||

| Vacant proportion, transformed | .04 (.01)* | −.06 (.01)* | −.02 (.01) | .04 (.01)* | ||||

| County mean income, transformed | .00 (.01) | .26 (.01)* | .05 (.01)* | .13 (.01)* | ||||

| Constant | .02 (.01)* | .06 (.03)* | .18 (.02)* | .43 (.02)* | .07 (.01)* | .05 (.03) | −.03 (.01)* | .14 (.03)* |

| R2 | .0042 | .0647 | .2175 | .3727 | .0232 | .0414 | .0058 | .0874 |

| Number of respondents (counties) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) | 16,000 (200) |

Note: All counts, coefficients, standard errors, and R2 values are rounded on the basis of the Census Restricted Data Center protocols for model disclosures. The dependent variables are the number of unsafe or unhealthy conditions, the total monthly rent and utility payments, the proportion of total household income spent on rent and utility payments, and the racial proportion of the census tract matching the respondents’ race divided by the overall proportion of that racial category in the county.

*

Denotes that the coefficient is statistically significantly different from zero at p < .05.

Moreover, the tenant voucher program, politically marketed as the most advantageous public housing option, provides consistently lower quality units that are more segregated and at higher price points than the other HUD programs (see Figure 2). For example, the average tenant voucher holder spends 46 percent of their income on housing, only 2 percent lower than the average market rate renter and 10 percent higher than other HUD subsidy tenants. The voucher program also suffers from multiyear waiting lists (Leopold 2012; Sard and Alvarez-Sanchez 2011), unreasonable time frames and landlord requirements that leave tenants without housing (Finkel and Buron 2001; Pashup et al. 2005; Popkin et al. 2000; Sanbonmatsu et al. 2011; Wood, Turnham, and Mills 2008), power dynamics that result in unresolved maintenance issues (Briggs and Turner 2006; Popkin and Cunningham 2000; Wood et al. 2008), limited units because of inspection costs and requirements (Marr 2005; Pashup et al. 2005; Varady et al. 2013), and the concentration of vouchers in higher poverty neighborhoods (Boyd et al. 2010; Cunningham et al. 2018; DeLuca, Garboden, and Rosenblatt 2013; DeLuca, Wood, and Rosenblatt 2019; Garboden and Rosen 2019; Graves 2016; Oakley and Burchfield 2009; Popkin et al. 2000; Popkin and Cunningham 2000; Rosen 2014, 2020).

Public housing, especially as originally conceived, is not the problem. The problem is these benefits are still disproportionately afforded to White older adults while families of color are segregated into lower quality, higher cost units.

Conclusion

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Black, Chicanx, and American Indian scholars’ and activists’ direct-action campaigns and strategic lawsuits altered the public’s conception of what was “just” and pressured the federal government to mandate the desegregation and equal distribution of governmentally subsidized housing (Brown-Nagin 2022; Popkin et al. 2000; Taylor 2019). Yet even before the desegregation and equalization mandates took effect, the federal government began privatizing the management of subsidized housing and used racist stereotypes to demonize publicly managed complexes (Ellen 2020; Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). Government subsidized housing became increasingly associated with residents of color and, in particular, Black renters. Consequently, the public and the scholarly community ignored the fact that White renters remain the largest racial group among subsidized renters and failed to ask whether government subsidized housing programs were now racially equal and integrated.

The present study shows the consequences of these actions has been the continuation of separate and unequal public housing. Yet given the constraints of the available data, we are unable to uncover the exact procedures enabling the observed disparities. Future research should use HUD’s administrative data and ethnographic observations to investigate the bureaucratic processes that segregate residents across subsidy programs, neighborhoods, and even within complexes. Moreover, rather than assuming governmentally built and managed developments are substandard and communities of color are inherently inferior, scholars should empirically compare low-income housing options and support initiatives that provide safe, decent, and affordable housing.

This future research will hopefully illuminate specific interventions government agencies and elected officials can take to promote equity and integration within U.S. public housing programs. Yet even without these specificities, elected officials, journalists, and public intellectuals can deliberately alter the false narratives regarding failing public housing by celebrating how subsidized housing provides the safest and most affordable housing for low-income residents. Additionally, building on the findings in this research, government agencies should consider three concrete interventions: (1) integrating developments across age and family composition, (2) investing in upgrading AI/AN housing developments, and (3) reallocating resources from tenant vouchers into high-quality, well-managed public housing developments. Although these interventions cannot address all the observed inequities, they would begin to adjudicate the centuries-old injustice of subsidizing White residents’ housing while subjecting people of color to subpar, more expensive units.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research uses data from the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer Household Dynamics Program, which was partially supported by National Science Foundation grants SES-9978093, SES-0339191, and ITR-0427889; National Institute on Aging grant AG018854; and grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. This specific project was also funded by the Russell Sage Foundation under grant 1911-19390 and the University of New Mexico ADVANCE program.

ORCID iDs

Junia Howell https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4631-7225

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9513-8122

Footnotes

Disclaimer Views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the Census Bureau. The Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board and Disclosure Avoidance Officers have reviewed this information product for unauthorized disclosure of confidential information and have approved the disclosure avoidance practices applied to this release. This research was performed at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center under FSRDC Project Number 2080 (CBDRB-FY23-P2080-R10255).

1 Reflecting the continual evolution of racial groups, we adjust our terminology to reflect the historical period being discussed. For trends over time, we use contemporary discourse: Asian, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and White. For the empirical findings, we replace Indigenous with American Indian/Alaska Native, complying with the recommendations of the National Congress of American Indians. We capitalize all racial terminology to signify socially constructed proper nouns, not biological descriptive adjectives.

2 Building on the Housing and Urban Development Act, which allowed housing agencies to rent units from landlords, the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 revised Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937 to fund privately managed public housing. Congress expanded this further in 1976 to include vouchers (Vale and Freemark 2012; Winnick 1995). Vouchers were designed to comply with the 1976 Supreme Court desegregation mandate while appeasing White communities opposed to integrated public housing (Business and Professional People for the Public Interest 1991).

3 The academic discourse mirrored the political left’s attempt to seemingly support the civil rights movement while preserving racial segregation and fearing Black empowerment.

4 Scholarship was used to justify the 1983 revision of Section 8 that eliminated new construction and expanded the tenant voucher program (U.S. Congressional Research Service 2014; Winnick 1995); the Tax Reform Act of 1986 that gave the largest housing subsidy in history to wealthy investors providing the capital for low-income housing developments (Johnson 2016); the 1993 Urban Revitalization Demonstration (later renamed HOPE VI) program, which replaced existing publicly funded complexes with mixed-income decentralized developments (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021); and the 1998 expansion of the housing choice voucher program (Schwartz 2021).

5 In the early 1950s, homeownership subsidies were more financially advantageous for many White low-income families. This resulted in an exodus from the all-White public housing complexes (Vale and Freemark 2012). Desiring to fill the growing number of empty units, policymakers expanded the eligibility criteria to include single older adults and disabled residents, which shifted the average age within these complexes while maintaining their racial demographics.

6 The 2017 HUD income eligibility is determined by family size and location (see https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il.html`2017_data). For example, in Orlando, a family of two qualified if they made less than $37,400, while a family of six qualified if they made less than $54,200. In San Francisco, a family of two was eligible if their income was less than $84,300, and a family of six was eligible if their income was below $122,250. Families were excluded from the sample if they did not report household size, annual income, subsidy status, racial classification, or census tract or if their housing costs were improbable (e.g., out-of-pocket housing costs were 150 percent of their income or >100 percent of their income and >$1,000 monthly per room).

7 Specific definitions for each of these unsafe or unhealthy conditions can be found in the AHS codebook.

8 To clarify, HUD was not incorporated until 1965 but was charged with overseeing and funding the existing publicly built and managed developments.

9 Continuous and categorical operationalizations of this variable produced comparable results. We elected to use the continuous operationalization for parsimony.

10 In supplemental models, we examined whether the number of units substantively influenced results. The only notable distinction was between single family and multiunit structures.

11 We choose to use county mean income and not a measure of metropolitan affluence to ensure we could consistently measure regional wealth across both urban and rural areas.

12 For the models predicting number of unsafe conditions, we ran supplemental Poisson models to better capture the count data. Results were comparable with large effect sizes and smaller standard errors. We elected to use the more conservative linear regression models for consistency across the four dependent variables.

References

Banner Stuart. 2009. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Baptist Edward E. 2016. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books.

Bloom Nicholas Dagan. 2008. Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Boyd Melody L., Edin Kathryn, Clampet-Lundquist Susan, Duncan Greg J. 2010. “The Durability of Gains from the Gautreaux Two Residential Mobility Program: A Qualitative Analysis of Who Stays and Who Moves from Low-Poverty Neighborhoods.” Housing Policy Debate 20(1):119–46.

Briggs Xavier de Souza, Turner Margery Austin. 2006. “Assisted Housing Mobility and the Success of Low-Income Minority Families: Lessons for Policy, Practice, and Future Research.” Journal of Law and Social Policy 1(1):25–61. Retrieved from http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol1/iss1/2.

Brown-Nagin Tomiko. 2022. Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality. New York: Knopf Doubleday.

Business and Professional People for the Public Interest. 1991. “What Is Gautreaux?” Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://www.bpichicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/what-is-gautreaux.pdf.

Cortelyou George H. 2001. “An Attempted Revolution in Native American Housing: The Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act.” Seton Hall Legislative Journal 25:429–68.

Cunningham Mary K., Galvez Martha M., Aranda Claudia, Santos Robert, Wissoker Douglas A., Oneto Alyse D., Pitingolo Rob, et al. 2018. “A Pilot Study of Landlord Acceptance of Housing Choice Vouchers.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

DeLuca Stefanie, Duncan Greg J., Keels Micere, Mendenhall Ruby M. 2010. “Gautreaux Mothers and Their Children: An Update.” Housing Policy Debate 20(1):7–25.

DeLuca Stefanie, Wood Holly, Rosenblatt Peter. 2019. “Why Poor People Move (and Where They Go): Reactive Mobility and Residential Decisions.” City and Community 18(2):556–93.

DeLuca Stefanie, Garboden Philip M. E., Rosenblatt Peter. 2013. “Segregating Shelter: How Housing Policies Shape the Residential Locations of Low-Income Minority Families.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 647:268–99.

Desmond Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Crown.

Du Bois William Edward Burghardt. 1899. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dunbar-Ortiz Roxanne. 2014. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon.

Dunbar-Ortiz Roxanne. 2021. Not “a Nation of Immigrants”: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion. Boston: Beacon.

Ellen Ingrid Gould. 2020. “What Do We Know about Housing Choice Vouchers?” Regional Science and Urban Economics 80:103380.

Faber Jacob. 2020. “We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography.” American Sociological Review 85(5):739–75.

Faber Jacob William, Mercier Marie-Dumesle. 2022. “Multidimensional Discrimination in the Online Rental Housing Market: Implications for Families with Young Children.” Housing Policy Debate.

Finkel Meryl, Buron Larry. 2001. “Study on Section 8 Voucher Success Rates: Volume I Quantitative Study of Success Rates in Metropolitan Areas.” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/sec8success_1.pdf.

Fleming Crystal Marie. 2018. How to Be Less Stupid about Race: On Racism, White Supremacy, and the Racial Divide. Boston: Beacon.

Garboden Philip M. E., Rosen Eva. 2019. “Serial Filing: How Landlords Use the Threat of Eviction.” City & Community 18(2):638–61.

Goetz Edward G. 2018. The One-Way Street of Integration: Fair Housing and the Pursuit of Racial Justice in American Cities. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gotham Kevin Fox. 2000. “Separate and Unequal: The Housing Act of 1968 and the Section 235 Program.” Sociological Forum 15(1):13–37.

Graves Erin. 2016. “Rooms for Improvement: A Qualitative Metasynthesis of the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Housing Policy Debate 26(2):346–61.

Hannah-Jones Nikole. 2012. Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law. New York: ProPublica.

Howell Junia. 2019. “The Unstudied Reference Neighborhood: Towards a Critical Theory of Empirical Neighborhood Studies.” Sociology Compass 13(1):e12649.

Howell Junia, Emerson Michael O. 2017. “So What ‘Should’ We Use? Evaluating the Impact of Five Racial Measures on Markers of Social Inequality.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 3(1):14–30.

Howell Junia, Emerson Michael O. 2018. “Preserving Racial Hierarchy amidst Changing Racial Demographics: How Neighbourhood Racial Preferences Are Changing While Maintaining Segregation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41(15):2770–89.

Imbroscio David. 2021. “Race Matters (Even More Than You Already Think): Racism, Housing, and the Limits of the Color of Law.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City 2(1):29–53.

Itzigsohn José, Brown Karida L. 2020. The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line. New York: New York University Press.

Johnson Jeremy. 2016. “Housing Vouchers: A Case Study of the Partisan Policy Cycle.” Social Science History 40(1):63–91.

Korver-Glenn Elizabeth, Locklear Sofia. Forthcoming. “‘I’m Not a Tenant They Can Just Run Over’: Low-Income Renters’ Experiences of and Resistance to Racialized Dispossessing.” Critical Sociology. Los Angeles, CA.

Korver-Glenn Elizabeth, Locklear Sofia, Howell Junia, Whitehead Ellen. 2023. “Displaced and Unsafe: The Legacy of Settler-Colonial Racial Capitalism in the U.S. Rental Market.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City.

Krysan Maria, Crowder Kyle. 2017. Cycle of Segregation: Social Processes and Residential Stratification. New York: Russell Sage.

Ladner Joyce A. 1971. Tomorrow’s Tomorrow: The Black Woman. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Ladner Joyce A. 1973. The Death of White Sociology: Essays on Race and Culture. New York: Vintage.

Lareau Annette, Goyette Kimberly. 2014. Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools. New York: Russell Sage.

Leonard Tammy. 2016. “Housing Upkeep and Public Good Provision in Residential Neighborhoods.” Housing Policy Debate 26(6):888–908.

Leopold Josh. 2012. “The Housing Needs of Rental Assistance Applicants.” Cityscape 14(2):275–98.

Leventhal Tama, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. 2003. “Moving to Opportunity: An Experimental Study of Neighborhood Effects on Mental Health.” American Journal of Public Health 93(9):1576–82.

Ludwig Jens, Duncan Greg J., Gennetian Lisa A., Katz Lawrence F., Kessler Ronald C., Kling Jeffrey R., Sanbonmatsu Lisa. 2013. “Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Low-Income Families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity.” American Economic Review 103(3):226–31.

Ludwig Jens, Liebman Jeffrey B., Kling Jeffrey R., Duncan Greg J., Katz Lawrence F., Kessler Ronald C., Sanbonmatsu Lisa. 2008. “What Can We Learn about Neighborhood Effects from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment?” American Journal of Sociology 114(1):144–88.

Marr Matthew D. 2005. “Mitigating Apprehension about Section 8 Vouchers: The Positive Role of Housing Specialists in Search and Placement.” Housing Policy Debate 16(1):85–111.

Massey Douglas, Denton Nancy. 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Massey Douglas S., Lundy Garvey. 2001. “Use of Black English and Racial Discrimination in Urban Housing Markets: New Methods and Findings.” Urban Affairs Review 36(4):452–69.

Oakley Deirdre, Burchfield Keri. 2009. “Out of the Projects, Still in the Hood: The Spatial Constraints on Public-Housing Residents’ Relocation in Chicago.” Journal of Urban Affairs 31(5):589–614.

Pashup Jennifer, Edin Kathryn, Duncan Greg J., Burke Karen. 2005. “Participation in a Residential Mobility Program from the Client’s Perspective: Findings from Gautreaux Two.” Housing Policy Debate 16(3–4):361–92.

Pattillo Mary. 2013. “Housing: Commodity versus Right.” Annual Review of Sociology 39(1):509–31.

Popkin Susan J., Buron Larry F., Levy Diane K., Cunningham Mary K. 2000. “The Gautreaux Legacy: What Might Mixed-Income and Dispersal Strategies Mean for the Poorest Public Housing Tenants?” Housing Policy Debate 11(4):911–42.

Popkin Susan J., Cunningham Mary K. 2000. “Searching for Rental Housing with Section 8 in Chicago Region.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://webarchive.urban.org/publications/410314.html.

Rendón María. 2019. Stagnant Dreamers: How the Inner City Shapes the Integration of the Second Generation. New York: Russell Sage.

Robinson Cedric J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Rosen Eva. 2014. “Rigging the Rules of the Game: How Landlords Geographically Sort Low-Income Renters.” City & Community 13(4):310–40.

Rosen Eva. 2020. The Voucher Promise. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rosen Eva, Garboden Philip M. E. 2022. “Landlord Paternalism: Housing the Poor with a Velvet Glove.” Social Problems 69(2):470–91.

Rosen Eva, Garboden Philip M. E., Cossyleon Jennifer E. 2021. “Racial Discrimination in Housing: How Landlords Use Algorithms and Home Visits to Screen Tenants.” American Sociological Review 86(5):787–822.

Ruechel Frank. 1997. “New Deal Public Housing, Urban Poverty, and Jim Crow: Techwood and University Homes in Atlanta.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 81(4):915–37.

Sanbonmatsu Lisa, Katz Lawrence F., Ludwig Jens, Gennetian Lisa A., Duncan Greg J., Kessler Ronald C., Adam Emma K., et al. 2011. “Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program—Final Impacts Evaluation.” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pubasst/MTOFHD.html.

Sard Barbara, Alvarez-Sanchez Thyria. 2011. “Large Majority of Housing Voucher Recipients Work, Are Elderly, or Have Disabilities.” Center on Budget and Policy Priority. Retrieved August 2, 2023. http://www.cbpp.org/research/large-majority-of-housing-voucher-recipients-work-are-elderly-or-have-disabilities.

Schwartz Alex F. 2021. Housing Policy in the United States. 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

Taylor Keeanga-Yamahtta. 2019. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

U.S. Congressional Research Service. 2014. “An Overview of the Section 8 Housing Programs: Housing Choice Vouchers and Project-Based Rental Assistance.” RL32284, February 7. Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL32284.html.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2019. “Calculating Rent and HAP Payments.” Retrieved August 2, 2023. https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PIH/documents/HCV_Guidebook_Calculating_Rent_and_HAP_Payments.pdf.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2021. “About HOPE VI.” Retrieved February 2021. https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/ph/hope6/about#2.

Vale Lawrence J., Freemark Yonah. 2012. “From Public Housing to Public-Private Housing.” Journal of the American Planning Association 78(4):379–402.

Varady David P., Wang Xinhao, Murphy Dugan, Stahlke Andrew. 2013. “How Housing Professionals Perceive Effects of the Housing Choice Voucher Program on Suburban Communities.” Cityscape 15(3):105–30.

Winnick Louis. 1995. “The Triumph of Housing Allowance Programs: How a Fundamental Policy Conflict Was Resolved.” Cityscape 1(3):95–121.

Wood Michelle, Turnham Jennifer, Mills Gregory. 2008. “Housing Affordability and Family Well-Being: Results from the Housing Voucher Evaluation.” Housing Policy Debate 19(2):367–412.

Biographies

Junia Howell (she/her) is an is an urban sociologist and race scholar who uses quantitative and qualitative tools to identify and dismantle the specific policies, processes, and practices that uphold White supremacy. Her work focuses on the housing industry and disaster relief. She currently holds a faculty position at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Ellen Whitehead (she/her) is an assistant professor of sociology at Ball State University who specializes in family sociology, social inequality, and race and ethnicity. Her research explores how families make ends meet through kin support, government assistance programs, crowd funding platforms, and informal work. Her research has been supported through grants from the Russell Sage Foundation, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Aspire Program at Ball State.

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn (she/her) is an assistant professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis. Her research focuses on the sources of racial, gender, and class inequality in and across housing markets and urban built environments. Her recent book, Race Brokers: Housing Markets and Segregation in 21st Century Urban America (2021, Oxford University Press), examines how and why contemporary real estate industries and professionals infuse racism in the housing exchange process.