Portland Chinatown vanishes—a foreshadow of the CID?

Source: https://nwasianweekly.com/2023/03/portland-chinatown-vanishes-a-foreshadow-of-the-cid/

MARCH 17, 2023 BY ADMIN

“It’s very difficult to tell the mom-and-pop businesses—sorry, it’s too late, the project team has moved on”

Suenn Ho, Urban Designer & Project Team Co-Lead

By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

They had planned it down to the type of trees they would plant—Chinese Windmill Palms—so that the restaurant owners wouldn’t have to worry about patrons slipping on fallen leaves or flower petals in the winter.

The redevelopment of the 10 city blocks that made up the national register New Chinatown/Japantown Historic District in Portland was so carefully orchestrated that, besides the trees, there were to be magnetic bollards they could remove to expand streets for cultural celebrations. They would have curbless streets for the same celebrations. And they even planned to add extensions to sidewalks for safer crossing of pedestrians.

Rents were expected to go up, of course, which pleased the property owners. And the businesses expected an influx of new patrons. So that was not a problem.

“Everyone had a heart in it, everyone had good intentions,” said Suenn Ho, an urban designer who co-led the project team. She also led community outreach and worked closely with the joint community-city development commission-city bureau of transportation in charge of development.

An extinction moment?

At a time when Sound Transit (ST) is on the cusp of making a decision about where to place a new regional transit hub—next to or outside the Chinatown-International District (CID)—the fate of the Portland Chinatown has become symbolic for many.

“For an urban enclave hub that is rich in culture and history, it is vitally important to plan and move forward with a heightened awareness of its vulnerability. A lot of mom and pop businesses don’t have a sense of just how vulnerable they are, and the city planners, they have a lot more means, but they don’t live on the ground and breathe with those businesses, either. The mom-and-pop businesses may just follow the experts’ lead.”

Suenn Ho, Urban Designer & Project Team Co-Lead

Some see it as a precursor to what may happen in Seattle should the ST board decide to build a major transportation project that will spill over into the CID with construction, traffic, noise, and dust for a decade or more—the erasure of one of the last Chinatowns in the nation.

Others argue Portland and Seattle are too dissimilar to compare.

Still others question the entire scenario—they say the CID can endure a decade of construction and will be richly rewarded with more direct transit connections.

Nevertheless, the fate of the Portland Chinatown, as a result of a transportation project that was on a far smaller scale than the one proposed for Fourth Avenue here—should the ST board choose the option closest to the CID—raises significant questions about responsibility down the line for unintended consequences.

Many of these concerns have already been raised by some business owners in the CID.

Other issues cannot be foreseen, or are passed over by officials and planners, with an urgency to keep decisions flowing, said Ho and others.

At the same time, local business owners, often following the guidance of experts who do not actually live in the CID may not fully understand how vulnerable they are.

In the case of Portland, said Ho, almost everyone was overly optimistic.

“It was like looking into the future with a blindfold on, or looking into the future with rose-colored glasses on,” she said.

Rose-colored glasses

Ho, who has lived all over the world and worked on projects on different continents, was the sole vote opposing the immediate activation of the streetscape plan in Portland in 2001.

Instead, she wanted the commission to spend its funds, first and foremost, ensuring that business would stick around the community. The money should be spent on long-term sustainable economic development, such as enhancing the store fronts, incentives to entice property owners to retain old-timer retail shops and avoid squeezing small shops in hopes of gaining high-rent retail tenants.

In the end, her doubts proved true.

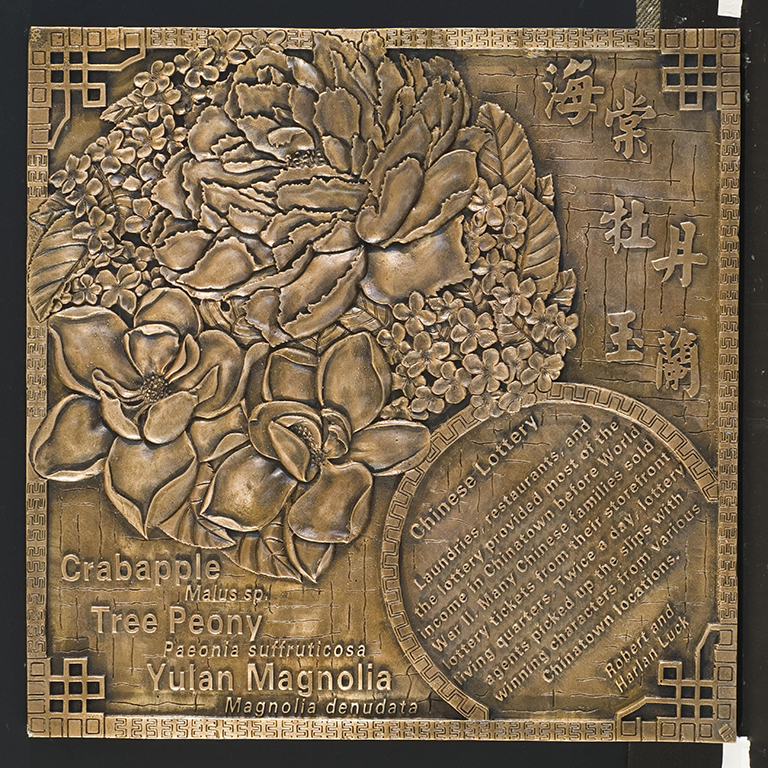

One of 20 bronze plaques urban designer Suenn Ho designed for the streetscape (Photo by Suenn Ho)

As a result of 18 months of construction, from early 2005 to late 2006, the planned streetscape had the reverse effect. It destroyed the community.

While streets were not shut down entirely, the obstacles created by construction, the loss of parking spaces and the dust created by jackhammering the streets, sent pedestrians and other patrons to other restaurants and businesses outside of Chinatown.

By the end of the project, the new design of the streets came out as planned. But the area was now mostly empty storefronts, said Ho.

Meanwhile, some property owners, who had believed the promises of the project committee, vacated the last remaining couple of long-term small businesses and imposed enormous rent increases. They expected the remade district to be transformed into a newly thriving enclave, attracting spanking new businesses.

Before the construction, rent had been low and affordable for mom-and-pop businesses.

“But the project committee leaders said, the streetscape would transform the whole area, it will look great, and will bring in more business. It gave property owners a false sense of the future,” said Ho.

One high-end restaurant gave it a go, for a while, but no one else followed, and it had to close soon after. Ho said, at this point, it was the last opportunity for the city’s development commission to provide heavy incentives and to recruit businesses to fill the vacant storefronts all at once.

Meanwhile, social services in the neighborhood had been increasing, so there were more unhoused people sleeping in front of storefronts, which further alienated potential patrons.

“It did not play out the way it was envisioned,” said Ho. “There were so many economic development factors that were outside the streetscape beautification project scope.”

At the same time, issues raised at the outset were overlooked by powerbrokers. Perhaps in a similar way, business owners at a meeting coordinated by ST several months ago complained that there would be no one held accountable if the project contractor went over time or changed the streets that were closed down.

Said Ho, “When you bring concerns up at the very beginning—if you ask, “What if? Why not?”—the people in charge are saying, ‘We can’t worry about that now, that’s down the line.’ And yet the project team moves on after the festive grand opening celebration, but the property owners and people in the neighborhood are still there, they get stuck with the empty storefronts that could not find takers.”

Kids making rubbing from plaques put in to commemorate the redevelopment of Portland’s Chinatown (Photo by Suenn Ho)

No real comparison?

In deciding between the north-south and the Fourth Avenue options presented by ST, Connie So would opt for Fourth Avenue. So is president of the OCA Asian Pacific Advocates of Greater Seattle and a teaching professor in American Ethnic Studies at the University of Washington.

“I think of Seattle as more comparable to San Francisco than to Portland. Both cities had actively recruited Chinese as laborers in the 19th century whereas Portland did not. Instead, Portland opted to recruit people from the Baltic region, because they want to keep it more white,” wrote So in an email.

So added, “This is one reason why Portland has a small Chinatown, whereas Seattle and San Francisco have larger Chinatowns. When I went to Berkeley, I experienced the 1989 earthquake. It devastated the Chinatown region, and many people wanted to ensure that the freeway or other subway access would be available for people wanting to visit Chinatown. This is a memory I refer to when I think about Chinatowns and light rail.”

Bringing travelers home?

Supporters of the Fourth Avenue option, in public comments at ST meetings, have argued that more people will come to the CID if a transit hub is stationed next door. They also say the CID needs direct connections to the airport and other parts of the region for the area to thrive again.

“A station at Fourth Avenue South serves as a connection point for travelers coming from—and going to—the Eastside, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and the rest of the region,” wrote Nora Chan, joined by several advocates from outside the community, in the Seattle Times last month.

“A station at Fourth Avenue South also provides the best opportunity to realize a shared vision for reactivating the area around Union Station and creating a safe, pedestrian-oriented neighborhood.”

Portland Chinatown today

The palm trees remain. And other improvements—or what seemed like improvements at the time—made by the city remain.

But the district is struggling with the increased presence of tents that occupy the sidewalks.

The last dim sum restaurant closed after 30 years in 2018.

Today, the streetlamps are still painted red—one of the “improvements” undertaken by the city, even though community leaders told them they didn’t match the grey and blue tones of the traditional Suzhou Chinese garden in the neighborhood.

The two bronze lions flanking the Chinatown gate once mistakenly painted gold—again by the city, because the “Foo dogs” looked too dark—are back to their original dark bronze patina.

The Portland Chinatown Museum, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon, and the Lan Su Chinese Garden, survivors of the exodus, have called for city officials to take action to remedy conditions.

Marie Wong, emerita professor of urban planning at Seattle University, wrote in a commentary in this paper in August, locals observed at the time that Chinatown had been remade at the expense of the Chinese.

“For an urban enclave hub that is rich in culture and history, it is vitally important to plan and move forward with a heightened awareness of its vulnerability,” said Ho. “A lot of mom and pop businesses, they don’t have a sense of just how vulnerable they are, and the city planners, they have a lot more means, but they don’t live on the ground. And the experts don’t live on the ground and breathe with those businesses, either. The mom-and-pop businesses may just follow the experts’ lead.”

She added, “It’s very difficult to tell the mom-and-pop businesses—sorry, it’s too late, the project team has moved on.”

The ST board is expected to announce its decision on March 23. To learn about how to attend the meeting, go to:

https://www.soundtransit.org/get-to-know-us/news-events/calendar/board-directors-meeting-2023-03-23

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.