Source Link: https://laist.com/news/la-history/why-a-property-worth-millions-was-returned-to-tongva-tribe

Published Oct 10, 2022 6:00 AM

On a secluded stretch of road in Altadena, several dirt paths lead off the street and converge on a lush one-acre property. A main house sits on the northwest corner of the parcel, with a guest house towards the middle. An outdoor fire pit faces east, towards a majestic view of Eaton Canyon.

The property is now owned by the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy, a nonprofit organization founded by members of the Gabrieleno/Tongva tribe, after being donated earlier this year. On a recent Friday, several members of the organization sat in the shade near the main house, sharing fresh blueberries and chatting.

Their plans for the space are future-oriented and nuanced; they include building a ceremonial area, returning the landscape to indigenous plants, and developing educational programs for younger members of the tribe, as well as the public.

“We see ourselves as descended from the land,” said Wallace Cleaves, the president of the conservancy. “Our duty to return that gift is to steward the land, which means to preserve it; to work with it, to make the land healthy.”

Understanding ‘Land Back’

Native Americans’ effort to reclaim stolen land has gained widespread media attention in recent years, largely under the umbrella term “land back.” But the struggle is not new; it dates back to the time of the initial land theft, which began when European settlers arrived in the mid- to late-1700’s and continued through the following several centuries.

“’Land back’ is one of those terms that’s kind of caught fire,” said Joely Proudfit, the chair and professor of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos. “What it means is, there isn’t enough land base for our Native peoples, especially here in California. So we need to be engaged in making sure that there’s an opportunity for the tribes of California to have some land returned.”

I didn’t want somebody to move in and … destroy the property. It’s quite special. And what my grandparents used it for was quite special. And I just thought it should go to somebody that’s going to honor that vision.

— Sharon Alexander

The Altadena property was donated by Sharon Alexander, whose grandparents purchased the parcel as a young couple. When she inherited it in 2015, Alexander — who lives in the South Bay and has no interest in moving — decided to give it back to the Tongva tribe, whose members lived in the area we now call Los Angeles for at least 10,000 years.

“I didn’t want somebody to move in and … destroy the property,” said Alexander. “It’s quite special. And what my grandparents used it for was quite special. And I just thought it should go to somebody that’s going to honor that vision.”

It’s one of the first private land returns to Native Americans in the Los Angeles area. The process of transferring the property hasn’t been without its challenges, but now, both giver and receivers hope it serves as a place for healing.

The Missionary Era

For millennia, Native Americans occupied Southern California, working and living with the land. But in the early 1770’s, Spanish missionaries descended on the region with the goals of converting Native Americans to Catholicism, forcing them to comply with European cultural norms, and turning them into subjects of the Spanish king.

Over the next several centuries, Native Americans’ land was stolen through violence, broken promises, force and manipulation.

“Settler-colonialism and capitalism and land exploitation has been something we’ve been dealing with for hundreds of years,” said Proudfit.

Spanish authorities initially told Native Americans that their land would be returned when the missions were complete. Instead, both the Mexican and Spanish governments began handing out land grants in the area, the vast majority of which did not go to Native people. Then, after California became part of the United States in 1847, treaties promising land to Native Americans were never ratified by the federal government.

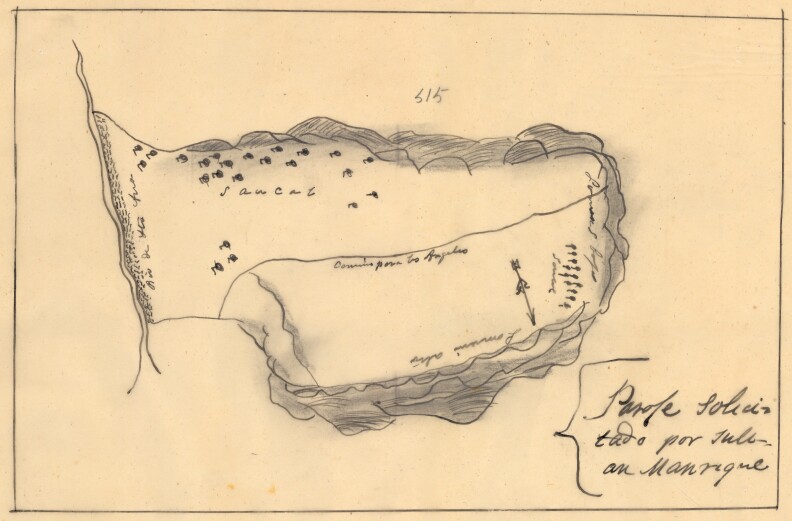

The family of Rudy Ortega Jr., the current Tribal President of the local Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, were victims of such theft. Ortega Jr.’s great-grandmother was one of few local Native Americans to hold a land grant, which included 4,400 acres in Encino and was originally in her father’s name. But in the late 1840’s, a local rancher and politician set his sights on those acres.

Historical documents suggest that the rancher paid two Native American families 50 pesos each in exchange for one-third of the Encino land grant, netting a massive profit after having sold a large plot in the area we now call Burbank. Soon, the name of Ortega Jr.’s grandmother, who was just 18 years old at the time, was no longer on the land’s title, despite not having sold all of her parcel.

“[My great-grandmother] disappears,” said Ortega Jr. “We don’t know why. But it lines up with our oral history. Her name appears to have been simply taken off the title. That’s how we lost that property.”

You don’t go from a bounty on your head and not being able to own property, to all of a sudden thriving. It takes generations to get over all of that genocide.

— Kimberly Johnson, Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy vice president

In the decades that followed, California Native Americans were systemically displaced, robbed and mistreated. An 1850 act legalized the indentured servitude of Native Americans. At around the same time, the state of California began formally offering a bounty of $0.25 for “Indian scalp[s],” which was later increased to $5.00.

Ortega Jr. said that his family has worked to reclaim their land ever since they were erased from the deed. But a legacy of deep injustice has made that almost impossible.

“You don’t go from a bounty on your head and not being able to own property, to all of a sudden thriving,” said Kimberly Johnson, the vice president of the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy. “It takes generations to get over all of that genocide.”

An Inheritance And A Decision

Sharon Alexander always had fond memories of the house in Altadena. Her grandparents, who met as part of a Jewish literary hiking club, built a dance pavilion on the grounds, hosted parties and worked tirelessly on the land.

“My grandmother spent her whole life out there working in this garden,” she said. “She had a medicinal herb area, a lot of citrus trees. I have wonderful memories there.”

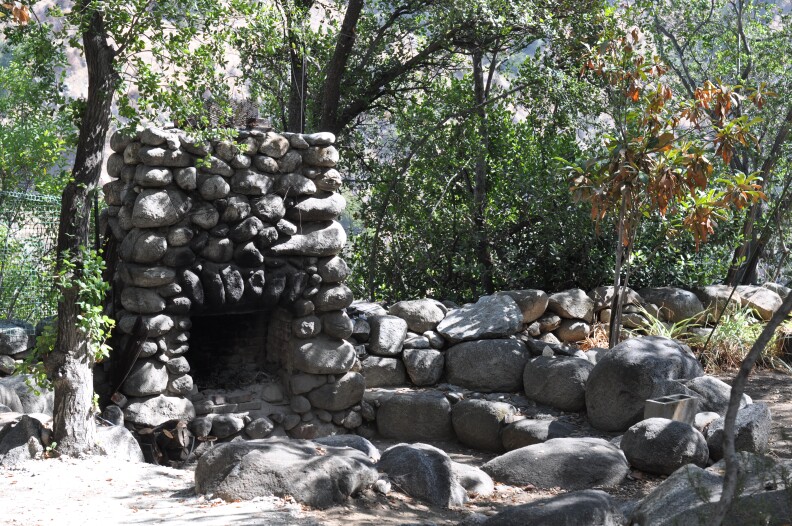

Alexander discovered that the land had originally been used by Native Americans when her grandmother told her about the property’s fire pit, which, her grandmother said, was once a tribe’s fire circle.

“She told me this as a kid,” said Alexander. “She mentioned that she had misunderstood, and ended up digging up this circle with whatever historical vestiges of the Native Americans were on it, and building the fire pit that she built.”

When Alexander inherited the property in 2015, an assessor estimated the land would be worth more than $2 million, she said. Knowing that a developer would almost certainly raze the parcel, Alexander decided to donate it back to the tribe.

As a person of Jewish faith whose community has also faced displacement and oppression, the donation was in line with Alexander’s spiritual values. She believes in the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, which translates in Hebrew to “repairing the world.”

“We’re very aware of trauma and intergenerational trauma that have been visited against our people,” she said. “I grew up in Los Angeles, and [I was] ignorant of the Holocaust that happened to this tribe. If I have a way to help fix that, and it’s in my ability to do that, I feel like my religion tells me to do that.”

She believes the donation also honors her grandmother’s legacy.

“She wanted to plant roots that were really grounded in the land,” said Alexander. “I know how pleased my grandparents would have been to see this land go to the tribe.”

Why It Was Complicated

The Altadena property donation wasn’t all smooth sailing. Since land repatriation is so rare, the tribe wasn’t initially equipped to process the bequest.

“We’ve never really had this happen before, so we didn’t have any of the infrastructure to receive the property or to deal with any of this, and it’s quite complicated,” said Cleaves.

Once the conservancy was set up, all appeared to be going according to plan. But land return is complicated, for both giver and receiver. It’s a big gift, and the property likely comes with a host of memories and emotions; some deeply personal and historic. Alexander’s family experienced anti-Semitism, and the home was a refuge. She has remained informally involved in shaping plans.

Many members of the Tongva tribe hope to keep decisions within their ranks, saying land sovereignty is of utmost importance.

Tony Lassos, a member of the conservancy’s board, notes that tribal members have previously worked with organizations whose donations came with strings attached. This is different.

“This is our first opportunity to have [land] without those strings,” he said. “This is a work of passion, of commitment to our community; we are all willing to get that done.”

For Cleaves, it’s about clearing a space to envision rituals that are carried out the ways they have been for millennia.

“Finally we have a place where we can actually conduct our own ceremonies, in our own ways, on our own terms, without having to work with restrictions,” he said.

All parties involved maintain hope for this rare arrangement. Reflecting on the possibilities inherent in the land once it has been revitalized and brought back to health and balance, Samantha Johnson, the conservancy’s first staff member, said she looks forward to nurturing new life.

“Now we can grow things,” she said. “This is how we take care of the land, and this is how it takes care of us.”

The Site Today And What’s Next

Members of the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy have been working for the better part of this year to clean out the property. The deed was transferred to the nonprofit in late March, and their visions for the space are slowly coming to fruition.

They’ve accepted their first artist-in-residence, part of whose job it will be to assist with caretaking of the land. They’re now able to store artifacts that have languished in garages and storage units, and they’re working with landscaping and environmental organizations to reimagine the space.

The valley of Eaton Canyon sits just beyond the property line, and conservancy members hope to build a staircase connecting the two. Education for younger tribal members is also on the docket, including how to steward the land, grow food and harvest it, and weave baskets.

The property will also serve as a central place for spiritual practices and ceremonies. “We have solstice and equinox ceremonies, and we have never been able to hold those on land that was ours, until now,” said Cleaves.

Wandering the paths that wind throughout the property, Johnson gestured to eucalyptus trees, which are not native to the area. Eventually, they plan to allow native plants to naturally flourish; it’s currently cactus fruit season, she said, and soon will be acorn season.

This work will allow the group to become reacquainted with their ancestral homeland — and it with them.

“It’s beautiful because now we have complete sovereignty over how we take care of it,” Johnson said. “As long as we take care of it, it will take care of us in return.”

This vision is staunchly in keeping with Native American traditions. Prior to European contact, tribes and villages worked in harmony with their land. That practice — along with the trauma and horror of settler-colonialism — is what has always driven land return efforts.

“This is our one home,” said Proudfit. “There is no other homeland or mother country. This is it for us. When people ask, ‘What do Native people want?’ It’s not equity. It’s land. It’s our homes. That means everything to us.”